A Canadian teenager from British Columbia is in critical condition after contracting the H5N1 bird flu virus, but health authorities have confirmed that the strain differs from the one currently circulating in U.S. dairy cattle. Genetic sequencing revealed that the virus responsible for the teenager’s illness belongs to a version found in wild birds, rather than the strain affecting cattle. Canada has been monitoring dairy cows for signs of the virus, but no infections have been detected in the country’s herds.

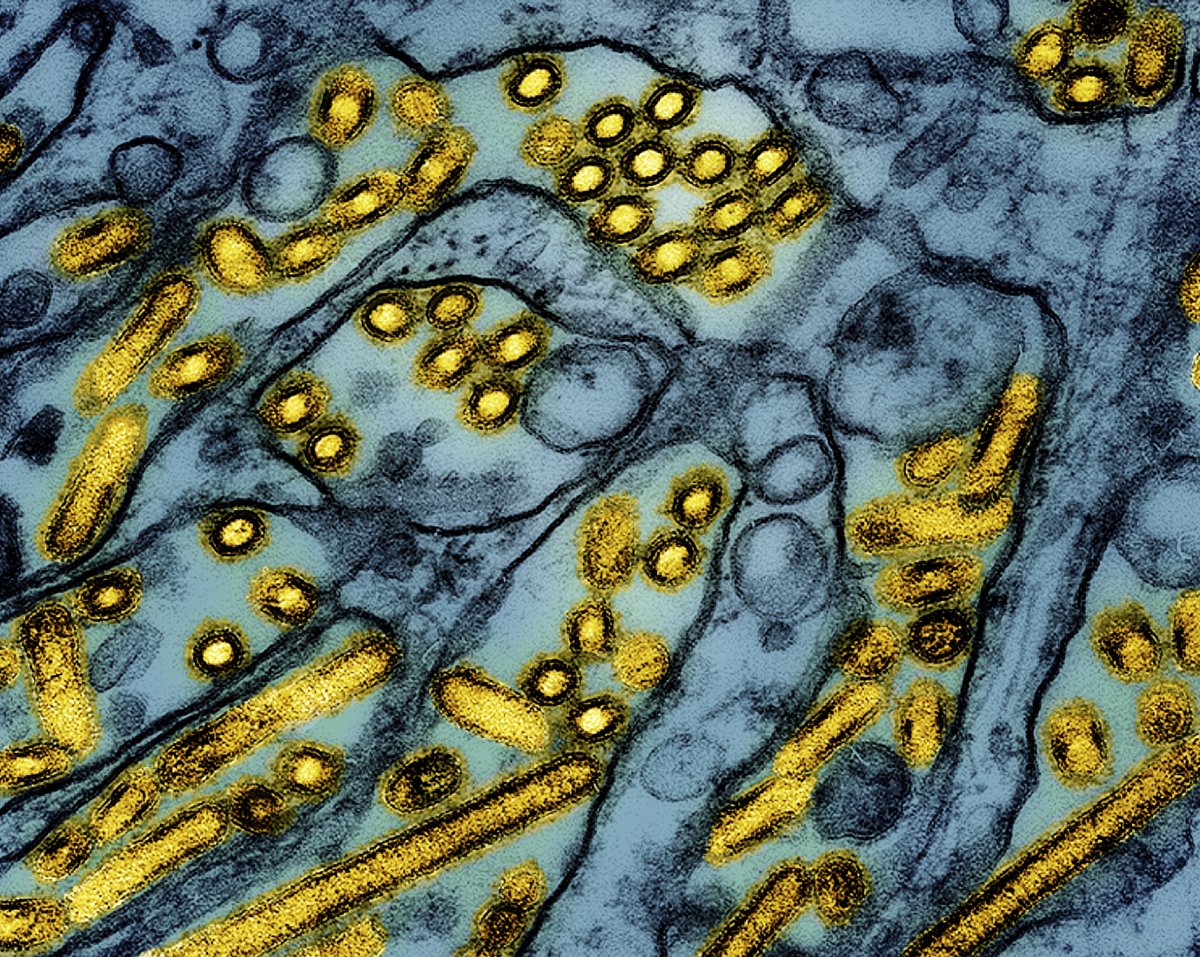

The H5N1 virus has evolved into multiple strains over the years, with the current version in U.S. cattle being the 2.3.4.4b genotype, identified as D3.13. In contrast, the Canadian teenager’s infection was caused by a 2.3.4.4b virus of the D1.1 genotype, which is primarily spread by wild birds. This strain has been responsible for several poultry outbreaks in places like Washington state. In British Columbia, the virus has led to 26 outbreaks in poultry operations, mainly concentrated in the Fraser Valley region, where the teenager lives.

The teenager is the first confirmed human case of H5N1 in Canada, though there was a previous fatal case in Alberta in 2014 when a person returning from China contracted the virus. Health officials in British Columbia are investigating how the teenager was infected but have not yet determined the exact source. While the teenager’s family reports no direct contact with infected poultry, the individual had interactions with various pets, including cats, dogs, and reptiles, none of which tested positive for the virus.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the infection’s origin, officials are hopeful it may be a rare, isolated case. Health authorities have been monitoring individuals who had close contact with the teenager to determine if there are any additional cases or signs of person-to-person transmission. So far, no other individuals have shown symptoms of the virus, which is considered rare to transmit between people. Experts like Bonnie Henry, British Columbia’s provincial health officer, have expressed cautious optimism, suggesting that the incident may not indicate a broader threat.

Health officials are continuing to test for antibodies in people who were in close contact with the teen, though it will take time to get results, as antibodies typically develop two weeks after exposure. Experts, including infectious disease consultant Allison McGeer, are reassured by the lack of further reported cases. Both Henry and McGeer remain hopeful that this infection is an isolated incident, with no broader outbreak or person-to-person transmission emerging in the region.