A teenager in British Columbia is critically ill in what appears to be Canada’s first human case of bird flu, specifically H5 avian influenza. The teen, who had no underlying health issues, is being treated in a children’s hospital after quickly deteriorating. Provincial Health Officer Bonnie Henry confirmed this during a news conference, emphasizing that the case highlights how bird flu can progress rapidly in young, otherwise healthy individuals. The situation is alarming given the rapid onset of severe symptoms, underscoring the potential for serious outcomes even in previously healthy patients.

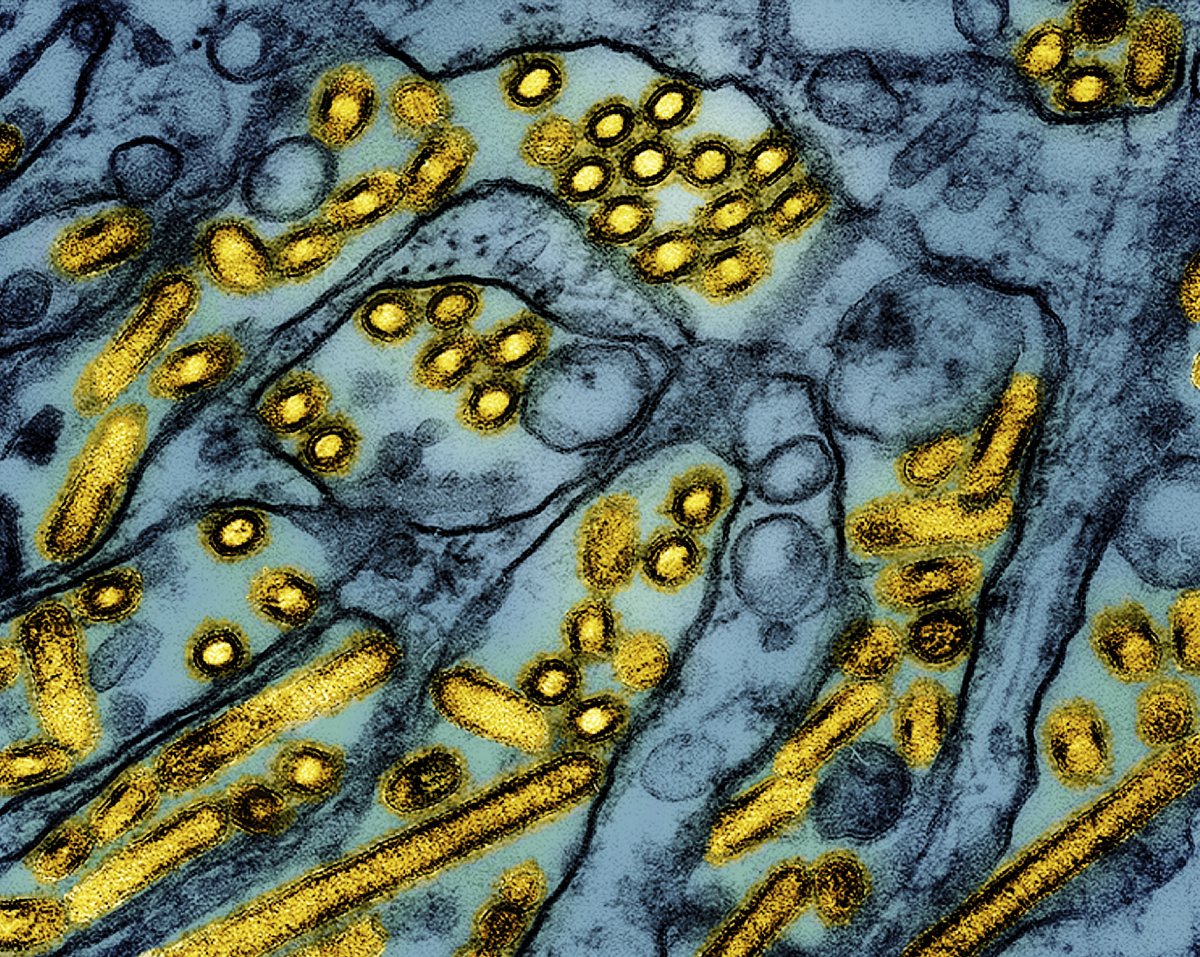

Health officials in British Columbia identified the infection as an H5 strain, though they are still working to pinpoint the specific subtype, with H5N1 being the presumed type. H5N1 bird flu is generally considered to have a low transmission risk for humans, as confirmed by the World Health Organization since it is typically not transmitted from person to person. However, the virus is spreading in various animal species, including cattle in the United States, adding a layer of concern for public health authorities as it expands beyond wild birds to other animal populations.

The teen’s symptoms first appeared on November 2, and by November 8, they were hospitalized after testing positive for bird flu. Symptoms included conjunctivitis, fever, and coughing, progressing to acute respiratory distress syndrome, which is often associated with severe respiratory infections. Health officials have not disclosed the teen’s age or gender, nor have they identified the source of the infection. The patient had not been exposed to farm animals but had contact with household pets, including dogs, cats, and reptiles, which are being examined as part of the ongoing investigation.

So far, health officials have tested about three dozen individuals who may have had contact with the infected teen, but no additional infections have been detected. This finding aligns with current evidence that bird flu does not easily spread between humans. However, experts warn that if the virus ever adapts to efficient human transmission, it could trigger a pandemic. Consequently, health agencies are closely monitoring cases like this and maintaining preventive measures to minimize the risk of broader transmission.

In response to the growing incidence of bird flu cases in animals, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently advised testing farm workers exposed to animals with bird flu, even if they have no symptoms, to monitor potential human cases proactively. Since March, bird flu has affected hundreds of dairy farms across 15 US states, leading to 46 identified human cases in the US since April. In Canada, British Columbia has confirmed 26 premises with affected wild birds, but no cases in dairy cattle, and there’s been no evidence of bird flu in milk samples. Canadian health authorities continue to track the spread and enforce biosecurity measures to prevent further infections.