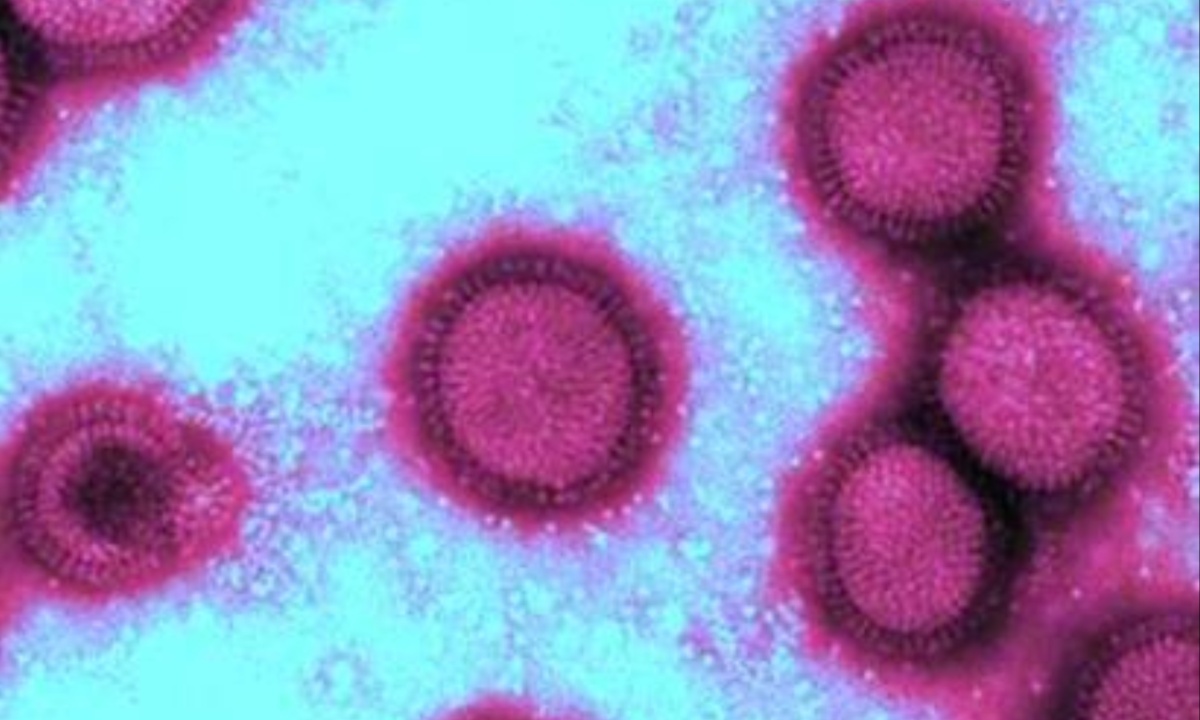

Viruses evolve rapidly, making them the fastest-evolving biological entities on Earth. This explains why annual flu vaccines are necessary, as seasonal influenza constantly evades immunity from prior vaccinations or infections. Some strains of the flu are particularly dangerous, such as the 1918 pandemic, which caused 50 million deaths and infected a significant portion of the global population. Subsequent influenza pandemics in 1957, 1968, and 2009 further underscore the ongoing threat influenza poses to public health.

Recent research led by Dr. Taia Wang at Stanford University has identified a critical factor influencing the severity of flu infections: the abundance of a specific sugar molecule, sialic acid, on antibodies. These antibodies are specialized proteins designed to block viruses from entering human cells. The study demonstrated that variations in the levels of sialic acid on these antibodies can determine whether a person experiences mild or severe flu symptoms. This discovery provides insight into a potential method to mitigate the effects of future influenza outbreaks.

The researchers discovered that a receptor on immune cells, CD209, can reduce inflammation during flu infections when activated by sialic acid-rich antibodies. This mechanism does not halt viral replication in lung cells but reduces the excessive inflammatory response often responsible for severe lung damage and impaired gas exchange in fatal cases of the flu. By dialing down this inflammation, the immune system’s response is better regulated, leading to improved outcomes even during viral replication.

Analysis of antibodies from flu-infected individuals revealed a stark difference between those with mild and severe cases. People with higher sialic acid levels in their antibodies had milder symptoms, while those with fewer sialic acid links tended to experience severe illness. These findings were validated in experiments with genetically modified mice, where sialic acid-rich antibodies significantly reduced lung inflammation and preserved respiratory function, even when exposed to lethal doses of diverse flu strains.

The study showed that sialic acid-rich antibodies bind to the CD209 receptor on alveolar macrophages in the lungs, a type of immune cell that patrols air sacs. This interaction shifts the macrophages’ response to anti-inflammatory, preventing the damaging effects of excessive inflammation. Typically, antibodies bind to pro-inflammatory receptors, which can exacerbate tissue damage and disease severity. By targeting the anti-inflammatory pathway, researchers demonstrated a new way to manage severe influenza.

This breakthrough has implications beyond influenza. The anti-inflammatory properties of sialic acid-rich antibodies are not limited to a specific flu strain or pathogen. This suggests that such antibodies could be used to treat other infectious diseases and even chronic inflammatory conditions. For example, sialic acid-enriched antibody fragments, already being explored for autoimmune diseases, proved effective in reducing flu severity in mice without relying on their pathogen-specific binding regions.

Age is a critical factor in antibody composition. Older individuals tend to have lower levels of sialic acid in their antibodies, which may explain the higher prevalence of chronic low-grade inflammation and age-related diseases, such as heart conditions, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer. This age-associated decline underscores the potential for therapies targeting sialic acid levels to improve health outcomes in aging populations.

The research team is now conducting longitudinal studies to assess whether sialic acid-enriched antibody markers can predict disease severity in humans. These findings could pave the way for novel treatments for influenza, other infections, and a wide range of inflammatory diseases, offering new hope for managing both acute and chronic health challenges. The study highlights how a deeper understanding of antibody composition can transform our approach to combating infectious and inflammatory diseases.