A boy with severe epilepsy has become the first patient globally to trial a new device implanted in his skull designed to control seizures.

The neurostimulator, which delivers electrical signals deep into his brain, has reduced Oran Knowlson’s daytime seizures by 80%.

His mother, Justine, told that Oran is happier and enjoys a “much better quality of life.”

The surgery, part of a trial at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, was performed in October when Oran, now 13, was 12 years old.

Oran, from Somerset, suffers from Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a form of epilepsy resistant to treatment, which he developed at the age of three.

Since then, he has experienced several daily seizures, ranging from a few dozen to hundreds.

When we first spoke with Oran’s mother last autumn before the surgery, she explained how epilepsy had dominated his life: “It has robbed him of all of his childhood.”

She described the various types of seizures Oran experienced, including ones that caused him to fall, shake violently, and lose consciousness. At times, he would stop breathing and need emergency medication to resuscitate him.

Oran also has autism and ADHD, but Justine says his epilepsy is the biggest challenge: “I had a fairly bright three-year-old, and within a few months of his seizures starting, he deteriorated rapidly and lost many skills.”

Oran is involved in the CADET project—a series of trials evaluating the safety and effectiveness of deep brain stimulation for severe epilepsy.

This collaboration includes Great Ormond Street Hospital, University College London, King’s College Hospital, and the University of Oxford.

The Picostim neurostimulator, developed by the UK company Amber Therapeutics, is used in this trial.

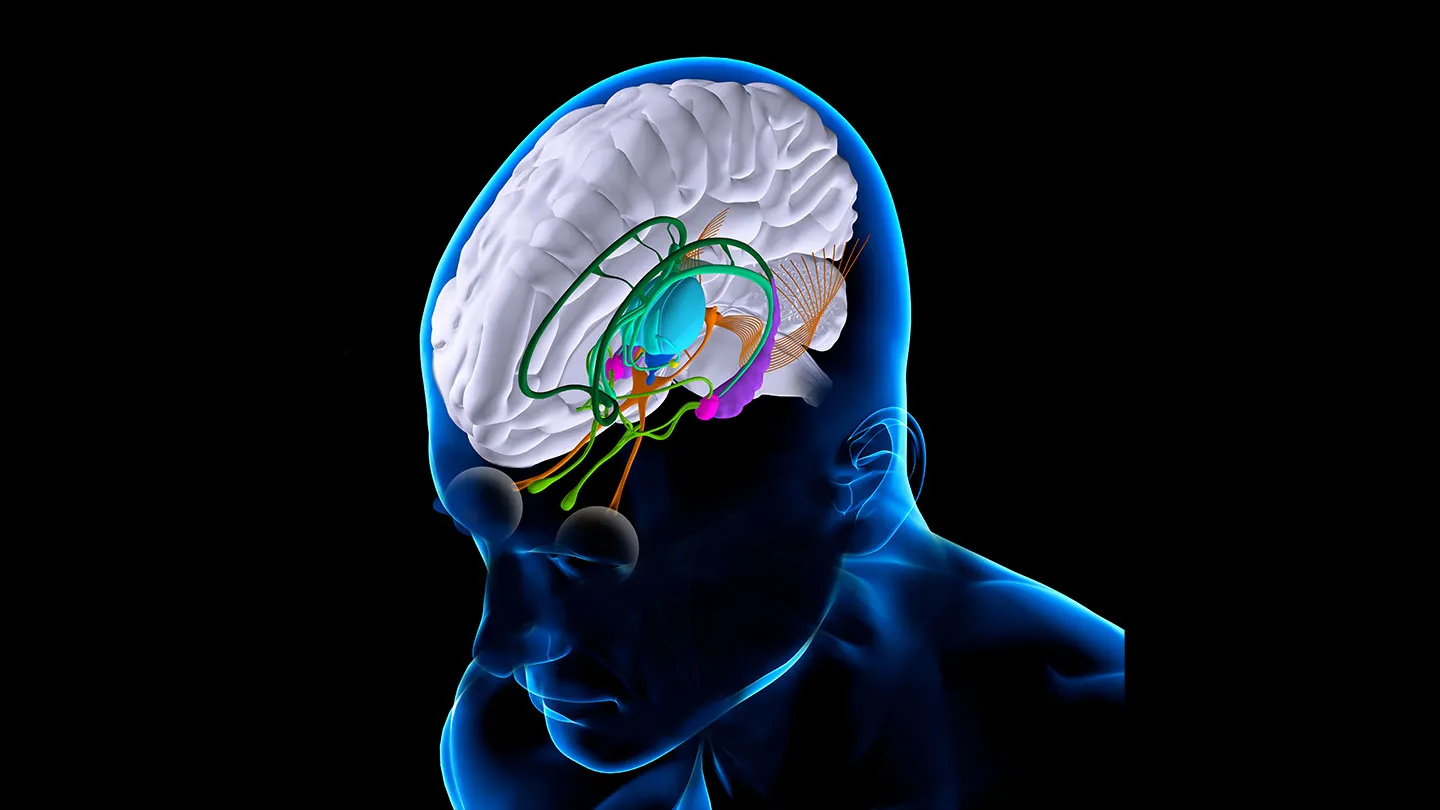

Epileptic seizures are caused by abnormal bursts of electrical activity in the brain. The neurostimulator emits a continuous current to block or disrupt these abnormal signals.

Before the operation, Justine expressed her hopes: “I want him to find some of himself again through the haze of seizures. I’d like to get my boy back.”

The surgery, which lasted about eight hours, took place in October 2023. Led by consultant pediatric neurosurgeon Martin Tisdall, the team inserted two electrodes deep into Oran’s brain until they reached the thalamus, a critical relay station for neuronal information.

The placement margin of error for the electrodes was less than a millimeter.

The electrodes were connected to the neurostimulator—a 3.5 cm square and 0.6 cm thick device—implanted in a space in Oran’s skull where bone had been removed. The device was then secured in place by screwing it into the surrounding skull.

Unlike previous attempts at deep brain stimulation for childhood epilepsy, where devices were implanted in the chest with wires running up to the brain, this new method places the device in the skull.

Martin Tisdall told: “This study is hopefully going to allow us to identify whether deep brain stimulation is an effective treatment for this severe type of epilepsy and is also looking at a new type of device, which is particularly useful in children because the implant is in the skull and not in the chest. We hope this will reduce the potential complications.”

This approach aims to lower the risk of post-surgery infections and device malfunctions.

Oran was given a month to recover before the neurostimulator was activated. When it is turned on, Oran does not feel it and can recharge the device daily using wireless headphones, while engaging in activities he enjoys, such as watching TV.

We visited Oran and his family seven months after the operation. Justine reported significant improvements: “He is more alert and has no drop seizures during the day.” His nighttime seizures are also “shorter and less severe.”

“I’m definitely getting him back slowly,” she said.

Martin Tisdall expressed his satisfaction: “We are delighted that Oran and his family have seen such a huge benefit from the treatment and that it has dramatically improved his seizures and quality of life.”

Oran is now taking riding lessons, which he enjoys. Although a nurse and a teacher are on hand for emergencies, they have not been needed so far.

As part of the trial, three more children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome will be fitted with the deep brain neurostimulator.

In the future, the team plans to make the neurostimulator respond in real time to changes in brain activity, aiming to block seizures as they are about to occur.

Justine expressed her excitement about the next phase of the trial: “The Great Ormond Street team gave us hope back…now the future looks brighter.”

Oran’s family understands that this treatment is not a cure, but they remain hopeful he will continue to recover from the effects of his epilepsy.

The Picostim neurostimulator, developed by Amber Therapeutics, is also used to treat Parkinson’s disease. Another type of skull-mounted neurostimulator has been used in the United States to treat epilepsy.