Since the earliest days of the pandemic, health officials have measured the threat of COVID-19 by comparing it to the flu.

Initially, the comparison wasn’t even close. In 2020, people hospitalized with the then-novel respiratory disease were five times more likely to die than patients hospitalized with influenza during the preceding flu seasons.

Immunity from vaccines and previous coronavirus infections has helped manage COVID-19 to the point that when researchers compared the mortality rates of hospitalized COVID-19 and seasonal influenza patients during the height of the 2022–23 flu season, they found that the pandemic disease was only 61% more likely to result in death.

Now, the same researchers have analyzed data for the fall and winter of 2023 and 2024. Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center at the VA St. Louis Health Care System, and his colleagues expected to find that the two respiratory diseases had finally equalized.

“There’s a narrative out there that the pandemic is over, that it’s a nothingburger,” Al-Aly said. “We came into this thinking we would do this rematch and find it would be like the flu from now on.”

The VA team examined electronic health records of patients treated in Veterans Affairs hospitals in all 50 states between Oct. 1 and March 27.

They focused on patients admitted because they had fevers, shortness of breath, or other symptoms due to either COVID-19 or influenza.

(People admitted for another reason, such as a heart attack, and then found to have a coronavirus infection weren’t included in the analysis.)

The COVID-19 patients were slightly older, on average, than the flu patients (73.9 versus 70.2 years old), and they were less likely to be current or former smokers.

They were also more likely to have received at least three doses of the COVID-19 vaccine and less likely to have avoided the shots altogether.

Yet after Al-Aly and his colleagues accounted for these differences and a host of other factors, they found that 5.7% of the COVID-19 patients died of their disease, compared with 4.2% of the influenza patients.

In other words, the risk of death from COVID-19 was still 35% greater than for the flu. The findings were published Wednesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“There is undeniably an impression out there that (COVID-19) is no longer a major threat to human health,” Al-Aly said. “I think it’s largely driven by opinion and an emotional itch to move beyond the pandemic, to put it all behind us. We want to believe that it’s like the flu, and we did—until we saw the data.”

Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious diseases specialist at UC San Francisco, said the study results align with what he sees in his hospital.

“COVID continues to make some people in our community very ill and die—even in 2024,” he said. “Although most will not get seriously ill from COVID, for some people it is like 2020 all over again.”

That’s particularly true for people who are older, who haven’t received their most recent recommended COVID-19 booster, and who haven’t taken full advantage of antivirals such as Paxlovid.

Chin-Hong noted that only 5% of the COVID-19 patients in the study had been treated with antivirals before they were hospitalized.

Even if the mortality rates for the COVID-19 and flu patients had been equal, COVID-19 would still be the bigger health threat because it is sending more people to the hospital, Al-Aly said.

Between Oct. 1 and the end of March, 75.5 out of every 100,000 Americans had been hospitalized with influenza, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During that same period, the hospitalization rate for COVID-19 was 122.9 per 100,000 Americans, the CDC says.

“COVID still carries a higher risk of hospitalization,” Al-Aly said. “And among those hospitalized, more will die as a result.”

Yet Al-Aly noted with frustration that while 48% of adults in the U.S. received a flu shot this year, only 21% of adults are up to date with their COVID-19 vaccinations, according to the CDC.

Chin-Hong added that more than 95% of adults hospitalized with COVID-19 this past fall and winter had not received the latest booster shot, according to the CDC.

Considering all the tools available to prevent hospitalizations and deaths—and especially the fact that they are readily available to patients in the VA system—the 35% relative risk of death from COVID-19 compared with the flu was “surprisingly high,” Chin-Hong said.

And it’s not like the flu is a trivial health threat, especially for senior citizens and people who are immunocompromised. It routinely kills tens of thousands of Americans each year, CDC data show.

“Influenza is a consequential infection,” Al-Aly said. “Even when COVID becomes equal to the flu, it’s still sobering and significant.”

The researchers also compared the mortality rates of VA COVID-19 patients before and after Dec. 24, when the omicron subvariant known as JN.1 became the dominant strain in the United States. The difference was not statistically significant.

In just the last two weeks, JN.1 appears to have been overtaken by one of its descendants, a subvariant known as KP.2.

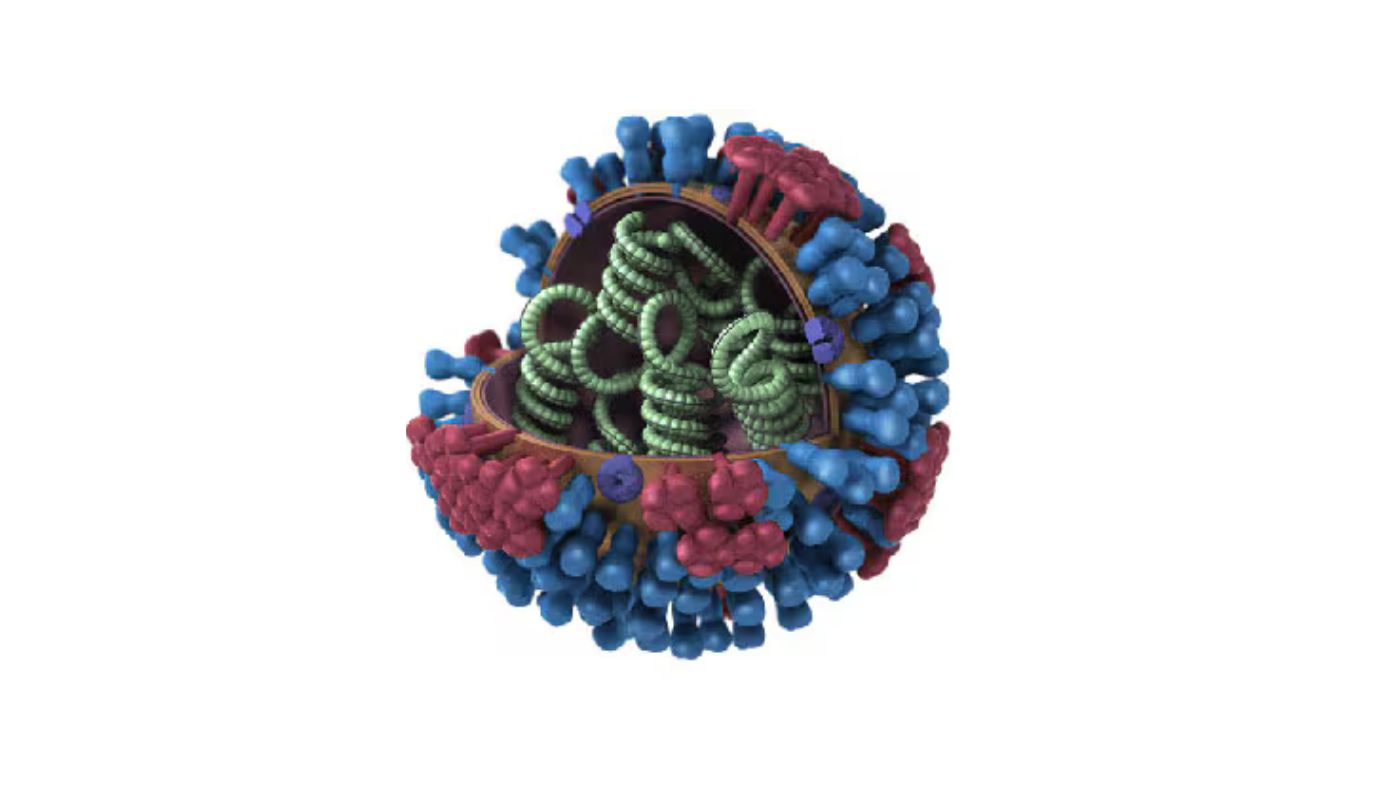

It’s part of a family of subvariants that’s taken on the nickname “FLiRT,” a moniker that references some of the mutations that have cropped up on the viruses’ spike proteins.

So far, there’s no indication that KP.2 is any more dangerous than JN.1, Al-Aly said.

“Are the hospitals filling up? No,” he said. “Are ER rooms all over the country flooded with respiratory illness? No.” Nor are there worrying changes in the amount of coronavirus detected in wastewater.

“When you look at all these data streams, we’re not seeing ominous signs that KP.2 is something the general public should worry about,” Al-Aly said.

It’s also too early to tell whether KP.2—or whatever comes after it—will finally erase the mortality gap between COVID-19 and the flu, he added.

“Maybe when we do a rematch in 2025, that will be the case,” he said.