These cases of Alzheimer’s disease presented an unusual pattern.

Firstly, the patients exhibited atypical symptoms for Alzheimer’s disease, with some even as young as their 30s, 40s, and 50s—considerably younger than typical onset ages for this condition.

Remarkably, they lacked the known genetic mutations that usually predispose individuals to early-onset Alzheimer’s.

However, these few patients shared a common history: during childhood, they had been treated with growth hormone derived from human cadavers’ brains.

This method was once used to treat various conditions causing short stature but was discontinued four decades ago when it was discovered that this treatment could inadvertently introduce protein fragments into the recipients’ brains. In some cases, this led to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a fatal brain disorder.

Interestingly, it wasn’t just the proteins linked to CJD that could be transferred. According to a report published Monday in Nature Medicine by the scientific team managing these patients, the growth hormone treatment seeded beta-amyloid proteins, which are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, into the brains of some recipients.

Decades later, these proteins developed into disease-causing plaques, marking the first known instances of transmitted Alzheimer’s disease. This discovery, while likely a scientific anomaly, adds complexity to ongoing debates about the root causes of Alzheimer’s.

“It looks real that some of these people developed early-onset Alzheimer’s because of that [hormone treatment],” said Ben Wolozin, an expert on neurodegenerative diseases at Boston University’s medical school, who was not part of the study.

External scientists affirmed the validity of these findings, noting that only those who received cadaveric growth hormone prepared in a specific manner—where protein fragments were not adequately eliminated—subsequently developed dementia.

Such cases are termed “iatrogenic,” indicating they result from a medical procedure. In conditions like iatrogenic CJD, the transmissible agents, known as prions, are misfolded proteins that act similarly to infectious agents.

While researchers debate whether beta-amyloid fits the definition of a prion, the authors of the study provide compelling evidence that, under exceptional circumstances, Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted through a mechanism resembling prion transmission, noted Mathias Jucker from the University of Tübingen and Lary Walker from Emory University in a commentary also published Monday.

Despite these findings, both the study’s authors and external researchers stressed that Alzheimer’s is not a contagious disease that can be transmitted through caregiving or other close contacts.

Moreover, the use of cadaveric growth hormone for treatment is no longer practiced; synthetic hormones have been the standard for decades.

The authors, who oversee a specialized prion disease research and treatment center in London, documented only five Alzheimer’s patients among the 1,800 individuals who received cadaveric growth hormone in the UK from 1959 to 1985.

Nonetheless, they believe these findings underscore the ongoing importance of rigorous practices like sterilizing neurosurgical instruments, which could potentially transfer prions if not properly cleaned between patients.

Beyond its scientific intrigue and as another consequence of cadaveric growth hormone use, these cases could reignite the long-standing, contentious debate about the origins of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We think from a public health point of view, this is probably going to be a relatively small number of patients,” said John Collinge of the MRC Prion Unit at University College London, the paper’s senior author.

“However, the implications of this paper we think are broader with respect to disease mechanisms — that it looks like what’s going on in Alzheimer’s disease is very similar in many respects to what happens in the human prion diseases like CJD, with the propagation of these abnormal aggregates of misfolded proteins and misshapen proteins.”

While many scientists acknowledge the role of beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s development and note recent therapeutic advances targeting its clearance from the brain, they also recognize that other factors likely contribute to the disease’s pathology.

“It raises questions about whether amyloid alone is able to cause problems,” said Marc Dhenain, an Alzheimer’s expert at the French research center CEA, who was not involved in the study.

External researchers acknowledged some puzzling aspects of the findings, citing limited information from only a few patients and incomplete data such as genetic sequencing and autopsy results.

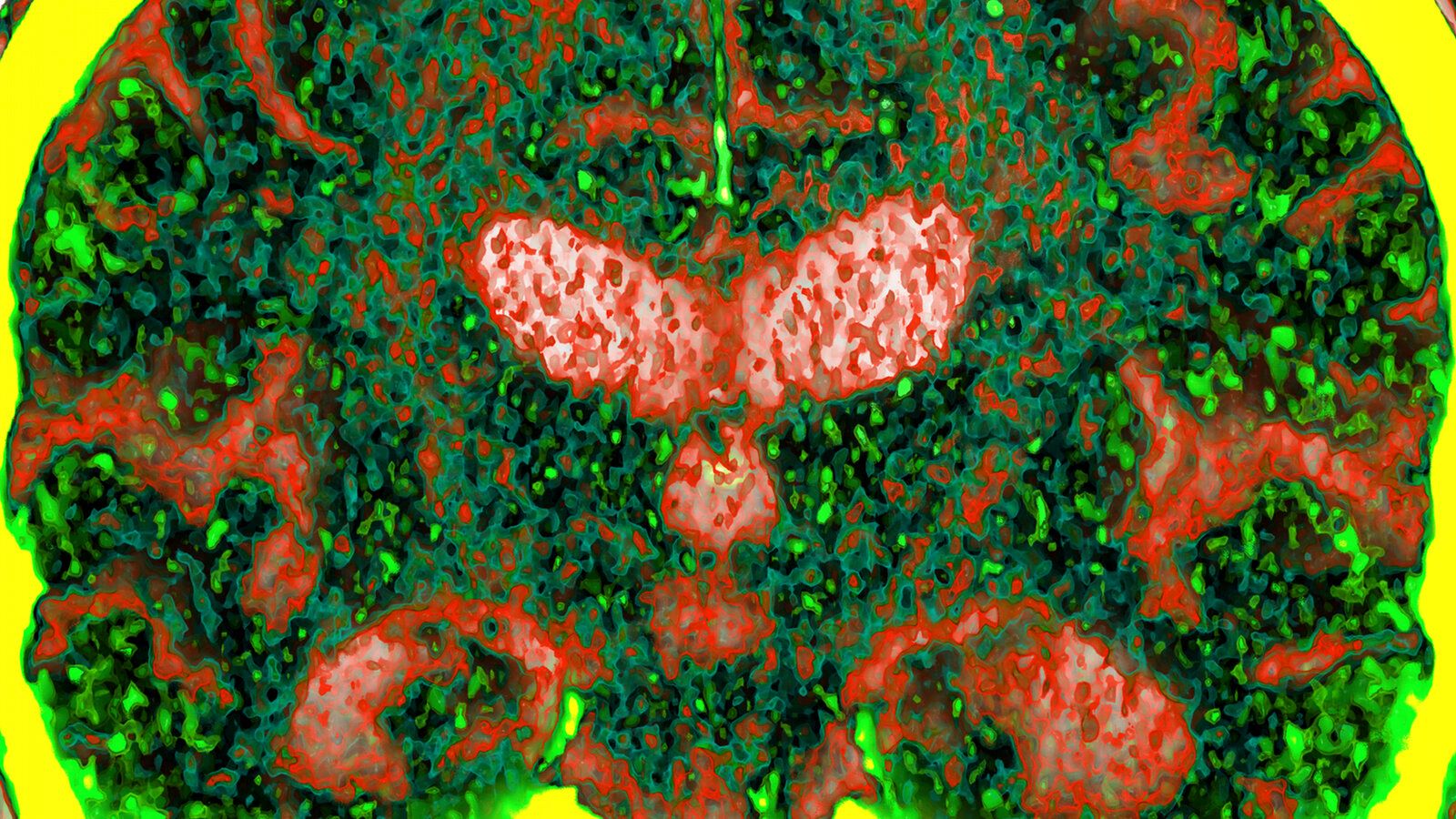

They noted the absence of significant brain inflammation in these patients, another hallmark of Alzheimer’s that is often associated with amyloid deposition.

Furthermore, they questioned why there was minimal presence of tau protein in the patients’ brains despite their cognitive decline, as tau levels typically correlate with cognitive impairment.

Some speculated that these patients may have harbored additional genetic mutations predisposing them to Alzheimer’s, with two patients having intellectual disabilities—a known risk factor.

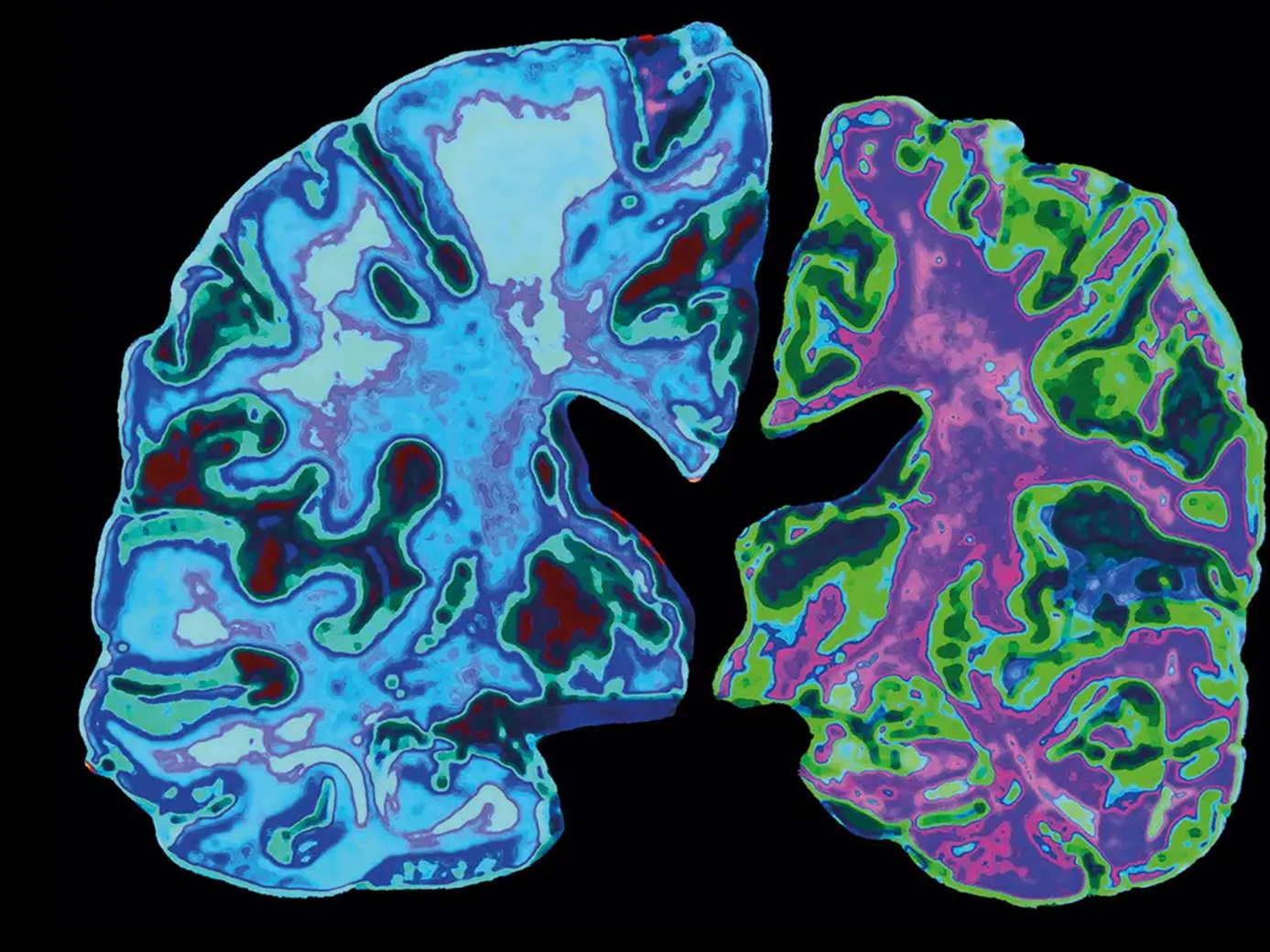

“Can the pathology be transmitted? Yes, it can, and that’s important conceptually,” Wolozin said. “The question is, what’s driving disease? There are many weird things about these rare cases. What’s unclear from the images is, why would they develop such severe dementia that quickly?”

Globally, more than 200 cases of iatrogenic CJD have been documented in recipients of cadaveric human growth hormone, primarily in France, the UK, and the US.

For years, researchers have gathered evidence suggesting an iatrogenic form of Alzheimer’s disease may also exist, though the vast majority of Alzheimer’s cases are sporadic, occurring among older individuals. Early-onset cases can also be linked to inherited mutations.

In 2015, UCL prion researchers reported finding substantial beta-amyloid deposits in the brains of patients who died from iatrogenic CJD, including build-up in brain blood vessels—an observation known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, prevalent in most Alzheimer’s patients.

This led them to speculate that the growth hormone administered to these patients might have been contaminated not only with CJD prions but also with amyloid seeds.

They further speculated that had CJD not claimed their lives, these patients might have eventually developed Alzheimer’s.

The paper details eight patients treated at the UK’s National Prion Clinic from 2017 to 2022. None of these patients had CJD, and only some were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

They had received the growth hormone treatment as children for various causes of short stature—ranging from brain tumors to developmental disorders to hormone deficiencies.

Among them, five were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or likely had the disease, with symptoms emerging between the ages of 38 and 55. Two others exhibited some cognitive impairment, while the third remained asymptomatic.

Researchers acknowledged that iatrogenic CJD cases often present differently from more common sporadic cases, suggesting that transmitted Alzheimer’s cases may also show distinct characteristics.

Gargi Banerjee, lead author of the study, highlighted that the researchers explored other potential causes of Alzheimer’s in these patients.

Given their young age at symptom onset, sporadic Alzheimer’s was unlikely, as this typically develops much later in life.

Genetic mutations known to cause early-onset dementia were absent in these patients, and their prior medical conditions, such as cancer treatment or congenital disorders, were not considered likely causes.

“The unique aspect about this group is that when you look at them together,” Banerjee said, “those who showed symptoms had diverse medical histories, but the only common thread was that they all received this specific type of growth hormone preparation in childhood. … There was no other unifying cause for this.”