A new study suggests that individuals who accumulate significant amounts of fat around their organs as they age may face a heightened risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

This type of fat, known as visceral fat, does not necessarily correlate with a high body-mass index (BMI).

Even individuals with healthy BMIs can harbor visceral fat around their organs, which is linked to brain changes potentially decades before any cognitive decline symptoms manifest, as presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

Dr. Cyrus Raji, the study’s senior author from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, highlighted the importance of moving beyond traditional measures like BMI to understand health risks associated with fat distribution.

He explained, “We need to move beyond traditional conceptions of body fat, like BMI, and really look at the specifics of how fat is distributed to understand the health risks.”

Visceral fat has been associated with systemic inflammation and increased insulin levels, both factors believed to contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Raji noted that confirming the presence of visceral fat typically requires an MRI scan of the abdomen, but there are signs that can indicate its accumulation, such as having a waist larger than the hips or increased blood sugar indicative of diabetes or prediabetes.

The study involved 54 cognitively healthy volunteers aged 40 to 60 with an average BMI of 32, considered obese according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

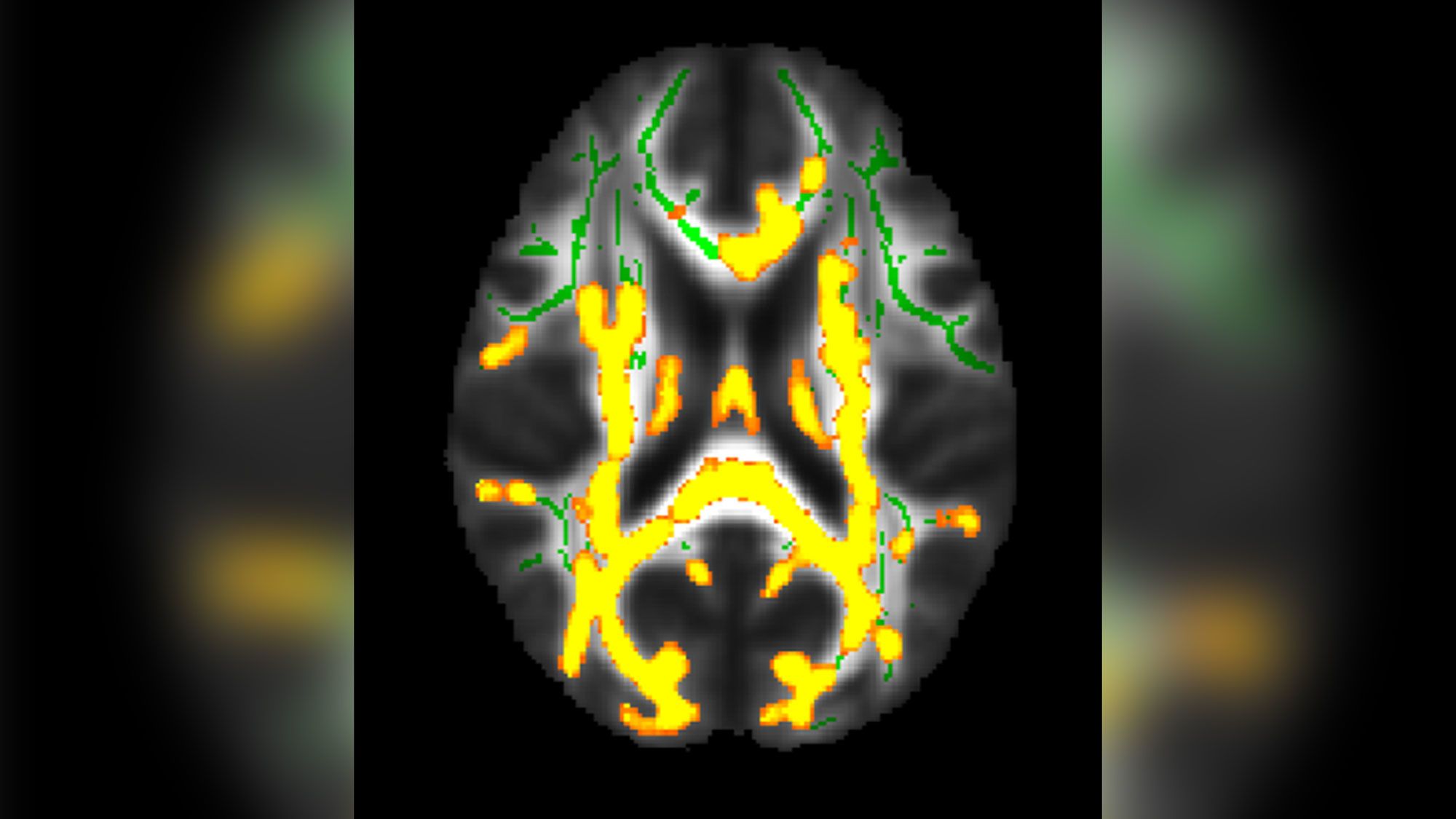

Researchers assessed various health parameters, including insulin and blood sugar levels, using MRI scans to measure fat levels around the organs and cortical thickness in the brain.

PET scans were employed to detect levels of amyloid and tau proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Analysis of the data revealed that participants with higher amounts of visceral fat tended to have greater accumulations of amyloid in their brains, suggesting a high risk of Alzheimer’s development.

Raji emphasized previous research indicating visceral fat’s link to inflammation and insulin resistance, which hinder the brain’s ability to clear amyloid proteins.

Given that Alzheimer’s disease may begin developing in the brain up to two decades before symptoms appear, the researchers plan to follow up with study participants over the long term to look into the impact of visceral fat accumulation.

Dr. Raji recommended aerobic exercise as the most effective means to reduce visceral fat, though it remains uncertain whether eliminating visceral fat can reverse its effects on the brain.

Specialists like Dr. Mary Ellen Koran from Vanderbilt University Medical Center underscored the importance of studies like this in establishing links between visceral fat and brain health.

While cautioning against preemptive abdominal scans for visceral fat based on current findings, experts like Dr. Joel Salinas from NYU Langone Health and Dr. Borna Bonakdarpour from Northwestern University stressed the potential benefits of identifying individuals at risk early to initiate preventive treatments.

Dr. Fanny Elahi from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai highlighted the preliminary nature of the study, emphasizing the need for larger-scale research before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

The study underscores the complex relationship between visceral fat and Alzheimer’s disease risk, suggesting a critical need for further investigation into its mechanisms and potential interventions.