Patients who underwent a minimally invasive procedure to replace a dysfunctional aortic heart valve with a new prosthetic valve showed comparable outcomes at five years to those who opted for traditional open-heart surgery, according to a new study.

Published in The New England Journal of Medicine and involving multiple international centers, including significant contributions from the Cedars-Sinai heart team, the study contributes to the ongoing discussion comparing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) to open-heart surgery.

“Our five-year data confirm that TAVR is a viable alternative to open-heart surgery for younger patients with aortic stenosis,” said Dr. Raj Makkar, MD, senior author of the study and vice president of Cardiovascular Innovation and Intervention at Cedars-Sinai’s Smidt Heart Institute.

“These findings support the routine use of TAVR, even in patients who are not considered high-risk for surgical complications.”

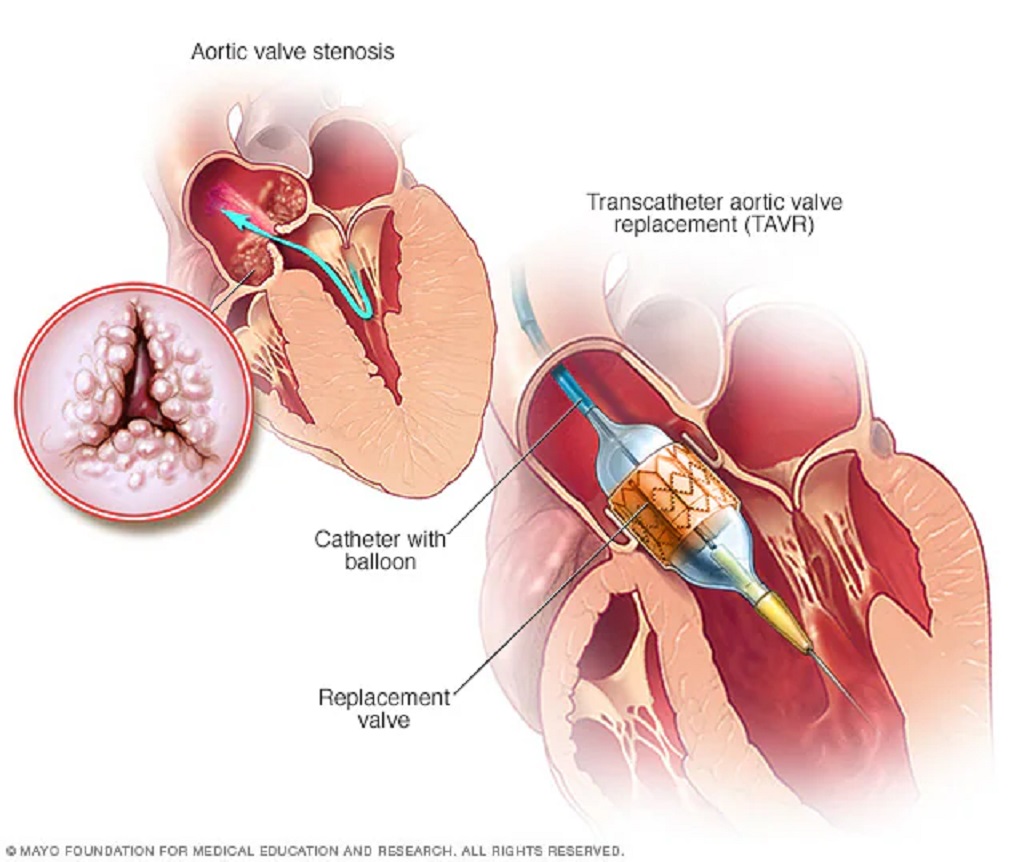

Aortic stenosis, a condition where narrowing in the aortic artery restricts the valve’s function, inhibits proper blood flow through the heart and body.

TAVR received FDA approval in 2011 for severe aortic stenosis patients at high risk for surgical complications. Over time, this minimally invasive option has increasingly been offered as an alternative to traditional surgery.

“These results align with the approach of the Smidt Heart Institute, where we tailor treatments to the specific needs of each patient,” noted Dr. Eduardo Marbán, MD, Ph.D., executive director of the Smidt Heart Institute.

“We provide a thorough evaluation of all treatment options, including both surgical and transcatheter procedures like TAVR.”

The PARTNER 3 clinical trial, which enrolled patients from various institutions in the U.S., Australia, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand, randomized 1,000 individuals with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis to undergo either TAVR or surgery.

Out of these, 496 patients underwent TAVR and 454 underwent surgery.

All patients were deemed at low risk for surgical complications. Researchers monitored their progress before and after the procedure or surgery, at discharge, 30 days post-treatment, six months later, and annually for five years.

The study found that rates of death, stroke, and rehospitalization after five years were similar in both groups.

Specifically, adverse events related to the new valve placement, the procedure itself, or heart failure occurred in 111 out of 496 TAVR patients and 117 out of 454 surgery patients.

These results corroborate earlier findings from other trials that compared outcomes between TAVR and surgery over shorter intervals (one, two, and three years post-treatment).

“The choice between TAVR and surgery should be individualized based on each patient’s anatomy, which can affect the initial procedure’s success and the feasibility of a potential repeat TAVR procedure years later as the first valve wears out,” added Dr. Makkar, who also holds the Stephen R. Corday, MD, Chair in Interventional Cardiology at Cedars-Sinai.

Researchers plan to continue following the study’s participants for a total of 10 years to assess the long-term durability of the prosthetic valves.