Scientists have identified a potential cause of “brain fog” in long COVID patients—persistent cognitive issues that hinder daily functioning long after infection.

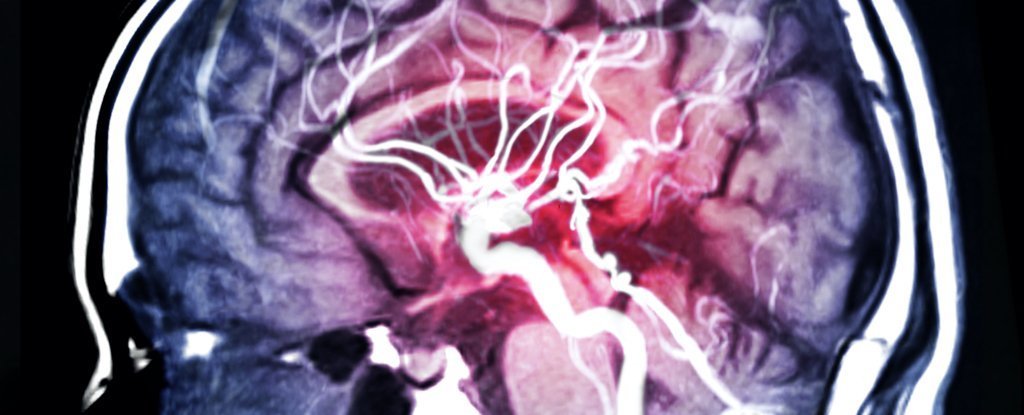

A new study suggests that these problems may be linked to blood clots triggered by the initial infection, similar to mechanisms observed in certain types of dementia.

These clots leave distinct protein markers in the blood, raising the possibility that testing for these markers could aid in predicting, diagnosing, and potentially treating long COVID.

Published in Nature Medicine, the findings propose that existing blood tests capable of detecting these proteins could assist clinicians in identifying long COVID cases, although experts caution that the symptoms and underlying causes of long COVID likely vary among individuals.

Up to 15 percent of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, develop lingering symptoms that persist for months or even years.

The condition presents challenges for treatment and diagnosis due to its diverse range of reported symptoms, including brain fog, fatigue, respiratory issues, and others.

It remains unclear whether the virus persists in the body or if the initial infection triggers subsequent reactions, such as autoimmune responses, leading to prolonged symptoms.

To investigate this, lead author Maxime Taquet, a psychiatrist from the University of Oxford, followed over 1,800 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in the UK between 2020 and 2021.

Researchers monitored these patients six and twelve months post-infection, conducting cognitive assessments designed to detect conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Analysis of blood tests taken during hospitalization revealed that patients experiencing brain fog six or twelve months after infection tended to exhibit higher levels of at least one of two proteins in their blood.

The first protein, D-dimer, indicates breakdown products of blood clots in the body. Although patients with high D-dimer levels reported memory issues, they did not show cognitive decline on tests; however, they were more likely to experience breathlessness and fatigue compared to other patients.

Taquet suspects these effects may be due to lung blood clots, potentially leading to reduced oxygen levels in the brain.

The second protein, fibrinogen, plays a role in clot formation to prevent bleeding and was found to be high in patients during active COVID infection. Individuals with heightened fibrinogen levels not only reported memory impairment but also demonstrated poorer cognitive performance on tests.

On average, this group scored below 86.7 percent six months post-infection—a result suggestive of dementia. Taquet suggests that either fibrinogen-induced blood clots in the brain or clots elsewhere in the body affecting the brain may contribute to severe cognitive symptoms.

Both D-dimer and fibrinogen are routinely tested worldwide, providing ample data for researchers to examine whether similar patterns occur in other patient groups. In a separate analysis, the team reviewed health records of nearly 50,000 individuals in the US, including those tested for D-dimer or fibrinogen before the pandemic.

They found that brain fog associated with high D-dimer levels was unique to COVID-19 patients. However, increased fibrinogen levels appeared to correlate with brain fog regardless of prior COVID-19 status, suggesting that cognitive issues associated with other conditions may also involve fibrinogen.

Resia Pretorius, a physiologist from Stellenbosch University, South Africa, finds the new findings “very exciting.”

Her research has previously linked brain fog in long COVID patients to “microclots” in the blood, often containing misfolded fibrinogen proteins that impede clot breakdown, potentially obstructing blood vessels and restricting oxygen flow to the brain and other organs.

Pretorius suspects that SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein interacts with fibrinogen, prompting structural changes.

Fibrinogen has previously been implicated in cognitive impairments, particularly in vascular dementia. Studies in mice have demonstrated that injections of fibrinogen can induce cognitive deficits.

Sidney Strickland, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Rockefeller University, notes uncertainties about whether dissolving clots can reverse brain damage or if oxygen deprivation permanently harms neurons.

Strickland suggests that clot-dissolving anticoagulants (commonly known as blood thinners) could potentially alleviate long COVID symptoms, although this approach has not been tested in clinical trials.

He cautions that these medications must be used cautiously due to the risk of serious bleeding. Strickland’s lab is developing antibodies targeting fibrinogen-specific pathways to avoid hemorrhaging associated with general anticoagulants.

He proposes that such treatments could be explored in long COVID patients, although clinical trials in dementia patients are still in the planning stages.

Despite the promising implications of the study, Avindra Nath, a neuroimmunologist at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, remains cautious about the role of blood clotting proteins in long COVID.

He points out that the study primarily involved hospitalized COVID patients with severe infections and likely organ damage. Nath’s own research has identified brain clots in COVID fatalities, but he stresses the need for further investigations into whether these clots directly cause symptoms.

In the interim, some physicians have observed that blood-thinning medications may benefit certain long COVID patients. David Joffe, a respiratory physician at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, Australia, prescribes anticoagulants based on their effectiveness in restoring brain function in some long COVID patients, despite the associated risks.

Joffe acknowledges the complexity of long COVID, noting its diverse symptomatology and underlying mechanisms triggered by the virus.

Joffe emphasizes that COVID-19 may instigate metabolic disturbances, brain inflammation, autoimmune responses, or immune suppression, each contributing to the multifaceted nature of long COVID symptoms.

He underscores the challenge of treating a condition with such diverse manifestations, describing long COVID as “many things” and highlighting the unique medical profiles of individual patients.

The intricate interplay of COVID-19 and its aftermath underscores the necessity for continued research to unravel its complexities.

Taquet and his team are leveraging brain imaging data from long COVID patients to pinpoint clot locations more precisely. They are also developing more sensitive cognitive tests to better understand how brain function deteriorates over time in these individuals.