Scientists have discovered a potential new antibiotic derived from a bacterium found in sandy soil in North Carolina, which may offer a novel approach to combating drug-resistant pathogens.

The newly identified compound, named clovibactin, was isolated by researchers at the pharmaceutical start-up NovoBiotic. Its mechanism of action suggests it could reduce the likelihood of pathogens developing resistance to antibiotics.

“While its development into a usable treatment is still about a decade away if proven safe, this discovery marks a significant step towards overcoming antibiotic resistance,” said Kim Lewis, a microbiologist from Northeastern University.

This discovery is particularly promising amid the global antimicrobial resistance crisis, which was the third leading cause of death worldwide in 2019 and is projected to contribute to ten million deaths annually by 2050.

However, cautious optimism is advised. “We’re at step one,” Lewis cautioned. “But the most significant aspect of clovibactin, beyond its potential as a drug candidate, is its contribution to expanding our understanding of antibiotics and what is achievable.”

The challenge of developing new antibiotics is compounded by the fact that 99 percent of bacterial species do not grow easily in laboratory conditions.

Using an innovative technique, Lewis and his team extended the incubation period of sandy soil isolates to encourage the growth of new bacterial strains. This led to the emergence of a new species, Eleftheria terrae carolina, from which clovibactin was isolated.

“Since clovibactin comes from bacteria that were previously uncultivable, pathogenic bacteria have not encountered such an antibiotic and thus had no opportunity to develop resistance,” explained Markus Weingarth, a chemist from Utrecht University.

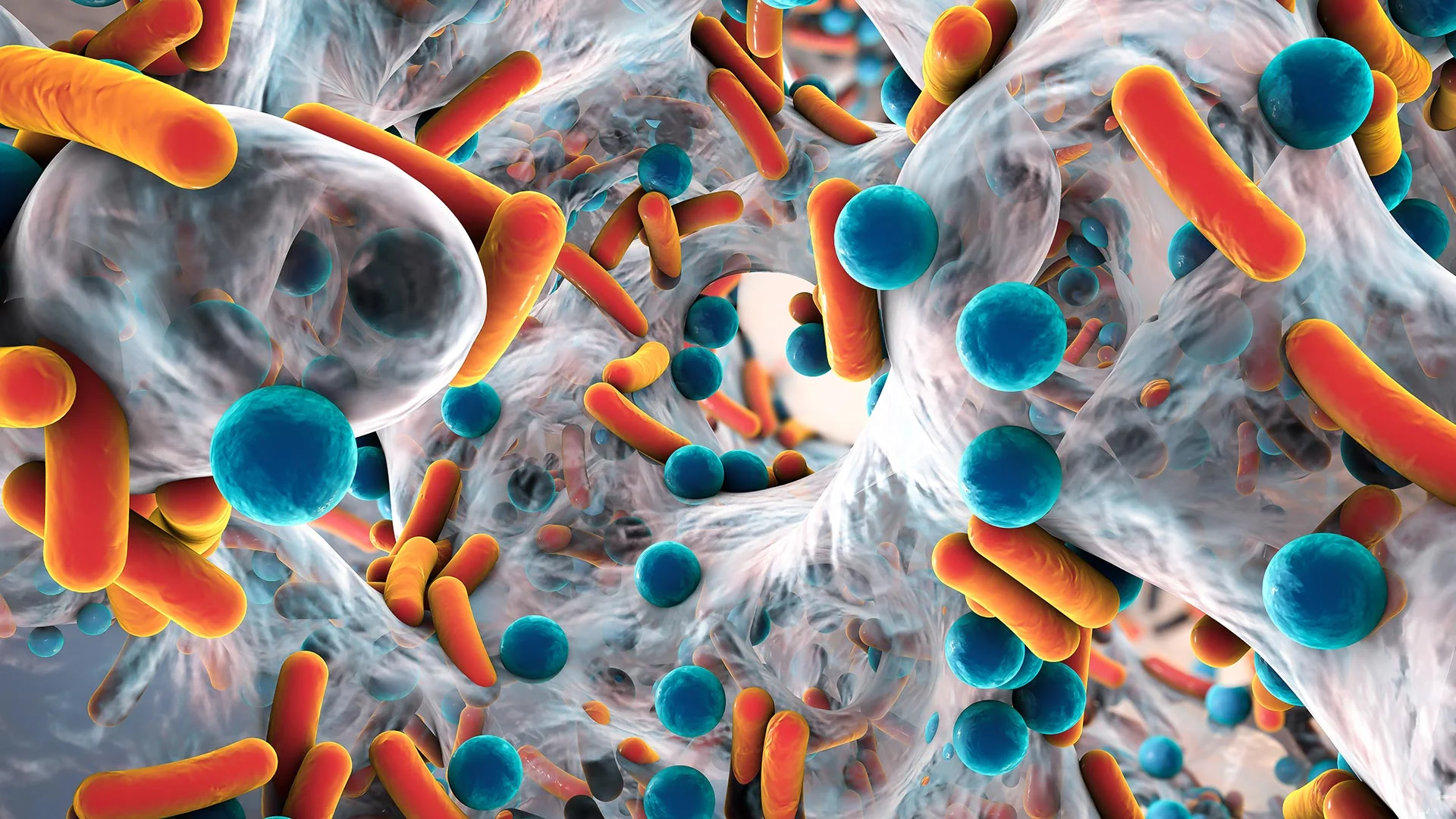

Clovibactin functions by binding to phosphate molecules on the bacteria’s cell envelope, where it gathers and attaches to peptidoglycan fibrils.

This interaction disrupts the bacteria’s cell membrane, prompting them to destroy their own membrane in an unsuccessful attempt to remove the compound.

“The most intriguing aspect is that clovibactin targets a simple and immutable phosphate molecule,” Lewis noted. “This is the first instance of a compound binding to such a straightforward target.”

Although bacteria can develop resistance through various mechanisms, clovibactin has shown promising results in clearing MRSA infections in mice and has proven non-toxic to human cells cultured in the lab. Importantly, resistance to clovibactin was not observed during these experiments.

“While there is still much work ahead, the research by Shukla and colleagues underscores the potential for developing long-lasting effective antibiotics,” the study concludes.