Mental illness and heroin derailed the life of Amber Webber, a gifted — if troubled — artist whose soulful paintings evoke Picasso.

After stints in rehab, Webber hoped to turn her life around, find a part-time job, and enroll in a graphic arts program at a South Florida college.

“Keeping going,” she wrote in her diary. “Keep going. Keep going.”

But one night last year, the 35-year-old disappeared into the bathroom of a Miami-area group home. A roommate discovered her lifeless body 15 minutes later.

Heroin didn’t kill Webber. Fentanyl did. But the Medical Examiner’s Office ruled she also died from xylazine — the potent animal tranquilizer known as “tranq” that’s become notorious nationwide for causing deep stupors and rotting flesh wounds that sometimes lead to amputations.

Authorities said a third substance also contributed to her death: meclonazepam, a drug with anti-anxiety properties developed to treat parasitic worms.

Webber’s death reflects the growing toll of fentanyl-tranquilizer mixes in the United States, where more than 3,000 people died of xylazine-related overdoses in 2021 — triple the fatalities recorded the previous year.

It’s also evidence of the evolving and unpredictable nature of the nation’s drug supply, dominated by fentanyl, but mixed with an ever-morphing array of synthetic substances that drug dealers use to stretch their supplies.

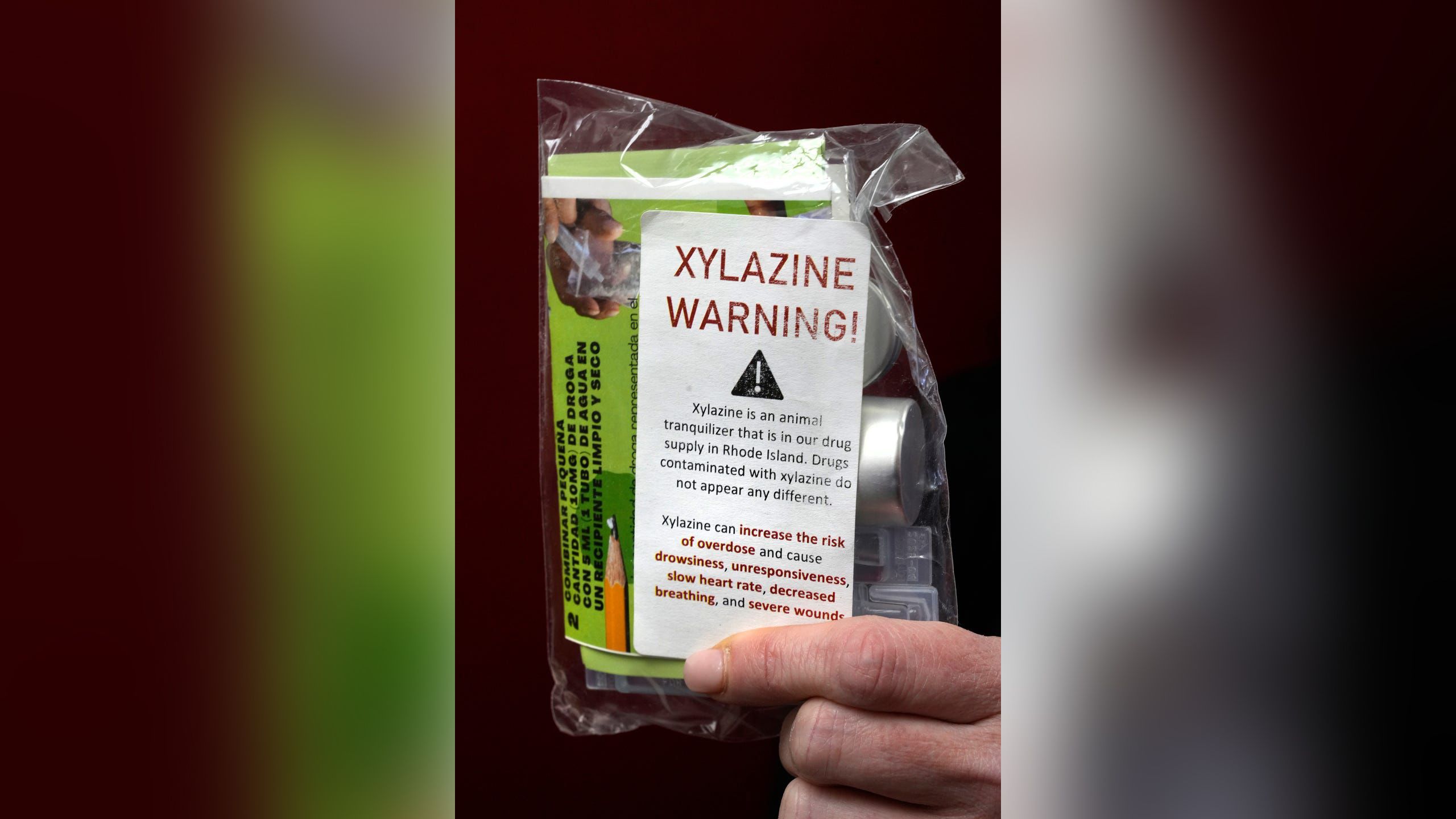

Many of those substances, like xylazine, pose their own health dangers and complicate efforts to reverse overdoses.

Those working to stop overdoses say that tracking what’s in street drugs is a frustrating game of whack-a-mole.

“It’s xylazine now. It could be something else tomorrow,” said Ryan McNeil, a public health and medicine professor at Yale University. “That’s the reality of the volatility of the drug supply.”

Webber’s family suspects she had no clue that her final hit of drugs contained xylazine or fentanyl. Investigators never determined if all three compounds were combined in a pill or a baggie of powder.

Her brother, Kurt Webber, 53, who battles opioid addiction himself, blames her death on the “trash market” of illegal drugs.

He lives in Palmyra, Pa., over an hour outside Philadelphia, where xylazine has emerged as a way for drug dealers to extend their supplies of fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that in 2021 killed over 70,000 people in the United States.

“It’s all designed to kill — this fentanyl, this xylazine, and all these other little spinoff drugs,” Kurt Webber said.

Researchers say that fentanyl, which has largely replaced heroin in many markets, is powerful but fast acting.

The xylazine gives it “legs,” extending the feeling of sedation by slowing one’s heart rate, breathing, and blood pressure.

Many users don’t realize their drugs contain xylazine, which can knock them out and make them susceptible to falls, robberies, or rapes.

Because it is not an opioid, xylazine does not respond to naloxone, the drug commonly used to revive people who are overdosing from opioids.

Xylazine, for now, isn’t a controlled substance under federal law, although a bipartisan group of lawmakers is proposing tightening regulations and the Food and Drug Administration has moved to crack down on importation.

In Florida, where Webber died, it has been a controlled substance since 2016, giving police authority to arrest those who sell it, although that hasn’t stopped it from proliferating.

The drug is used by veterinarians to sedate animals, particularly cattle and horses, but has never been approved for use by humans.

It popped up in illegal drugs in Puerto Rico in the early 2000s, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Over the last five years, it spread to the Northeast, particularly Philadelphia, where it has infiltrated more than 90 percent of street drugs, according to the Center for Forensic Science Research & Education, which posts an online early warning system about the latest drugs.

The DEA says its labs have now detected xylazine in drug seizures in 48 states. The number of xylazine-positive drug samples in the South, including Florida, rose by nearly 200 percent from 2020 to 2021, the agency reported.

It’s unclear how much of the xylazine mixed into illegal fentanyl is diverted from veterinarian stocks and how much is synthesized by clandestine chemists.

The DEA last fall said a kilogram can be purchased from online Chinese suppliers for between $6 and $20, allowing dealers “to reduce the amount of fentanyl or heroin used in a mixture.”

Amber’s brother Kurt — a charismatic former salvage diver who can rattle off details of ancient Spanish wrecks — recalled snorting fentanyl he believes was laced with xylazine while in a local Walmart several months ago.

Hours later, his worried girlfriend, Andrea Pullen, found him collapsed in a nearby field, breathing but comatose in subfreezing weather. She managed to wake him up and get him into her car.

“He definitely would have frozen to death,” Pullen said.

Others describe the ghastly black-and-purple wounds from prolonged use of “tranq dope.” In Maryland, April Tabor, 42, suffered sores for 13 months from xylazine-laced dope.

She received wound care through Voices of Hope Maryland, an addiction support group, but still lost feeling in her left hand from the infected sores.

In 2021, she began suffering nausea and fever but it wasn’t from opioid withdrawal.

“I started going septic,” Tabor said. “It took me three times of going to the hospital before I had to accept the fact that my arm was going to have to come off.”

Doctors amputated her infected left arm two inches below her elbow.

Deaths linked to fentanyl and xylazine show just how quickly drug combinations can penetrate illicit markets, surprising law enforcement, health officials, and users.

“Testing for xylazine is uneven across the United States, which makes it hard to get the national picture,” Rahul Gupta, director of the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy, said at a briefing this month as the White House designated the drug combination an “emerging public threat.”

In 2020, the DEA reported 808 overdose deaths nationwide in which xylazine was detected, a number that jumped to over 3,000 in 2021.

The deaths remain a small percentage of the over 107,000 U.S. overdose deaths in 2021, although officials acknowledge that not all toxicology departments routinely test for the sedative.

When xylazine is identified, forensic pathologists don’t always conclude it contributed to the cause of death.

Researchers say the tranquilizer would have to be consumed in large quantities to prove fatal on its own but admit more research is needed on how it contributes to mortality.

Even in places that routinely screen blood samples for xylazine, like Miami-Dade County, where Webber died, officials express surprise at the spike in overdose deaths tied to the animal sedative.

Last year, toxicologist Rocio Potoukian found that between 2015 and 2017, there were only four overdose deaths linked to xylazine. The number jumped to 169 between 2018 and 2022.

“One hundred percent of the cases also involved fentanyl,” Potoukian said.

For users in some parts of the country, more real-time testing is helping stave off fatal xylazine-and-fentanyl overdoses while ensuring proper wound care and addiction treatment.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Street Drug Analysis Lab tests drug samples — sent in from nearly 80 participating programs across 20 states — and posts results to its website, so users can check what compounds are being sold in their communities.