Oregon is currently experiencing its largest measles outbreak in more than 30 years, reflecting a nationwide increase in cases this year.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nearly one-third of all measles cases reported since the COVID-19 pandemic have occurred in just the past three months.

As of Tuesday, the number of cases in Oregon’s outbreak, which began in mid-June, had risen to 31, surpassing the state’s previous outbreak in 2019, when 28 cases were recorded.

Health officials attribute the resurgence of measles to declining rates of children receiving the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Outbreaks have predominantly occurred in communities where vaccination rates are low among children.

“Measles is one of the most contagious diseases we know, and the only way to prevent it is to maintain very high vaccination rates—above 95%,” said Paul Cieslak, medical director for communicable diseases and immunizations at the Oregon Health Authority’s Public Health Division.

“Two doses of the MMR vaccine offer lifelong protection for about 97% of those who receive it.”

All individuals infected during the current outbreak were unvaccinated, according to the Oregon Health Authority. Two people required hospitalization. This outbreak marks the largest in Oregon since measles was declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000.

Oregon’s outbreak is the second-largest in the nation this year, with 13 measles outbreaks reported across the U.S.

As of Tuesday, the CDC had documented 236 measles cases in the country over a period of just over eight months, compared to 58 cases reported in the entirety of 2023.

Nationwide, 87% of this year’s cases involved individuals who were either unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown.

Earlier in the year, measles outbreaks occurred in a Florida elementary school and a migrant shelter in Chicago.

Only Illinois and Minnesota have reported more cases than Oregon, with Illinois tallying 67 cases, Minnesota reporting 41, and Oregon with 31.

Illinois declared its outbreak, which began in March, to be over by early June. However, health officials in Oregon anticipate their outbreak will continue for some time.

“We don’t have enough vaccinated individuals to stop the transmission, so it continues to spread,” Cieslak said during an August 8 news briefing.

Oregon public health authorities have observed a growing trend of families seeking exemptions from vaccines, creating conditions that allow the highly contagious virus to continue circulating.

State data shows that since 2000, the rate of non-medical exemptions for kindergartners has risen from 1% to 8.8%. Experts assert that a 95% vaccination rate is necessary to achieve herd immunity and halt the spread of measles. The national average for kindergartner immunization is around 93%.

Health professionals note that measles transmission is concentrated in areas with clusters of unvaccinated individuals. They advise parents to check their children’s school immunization records.

With students returning to school, officials warn that unvaccinated children who are exposed to measles may need to stay home for up to 21 days, the incubation period for the disease. If they become ill, this exclusion period could be extended.

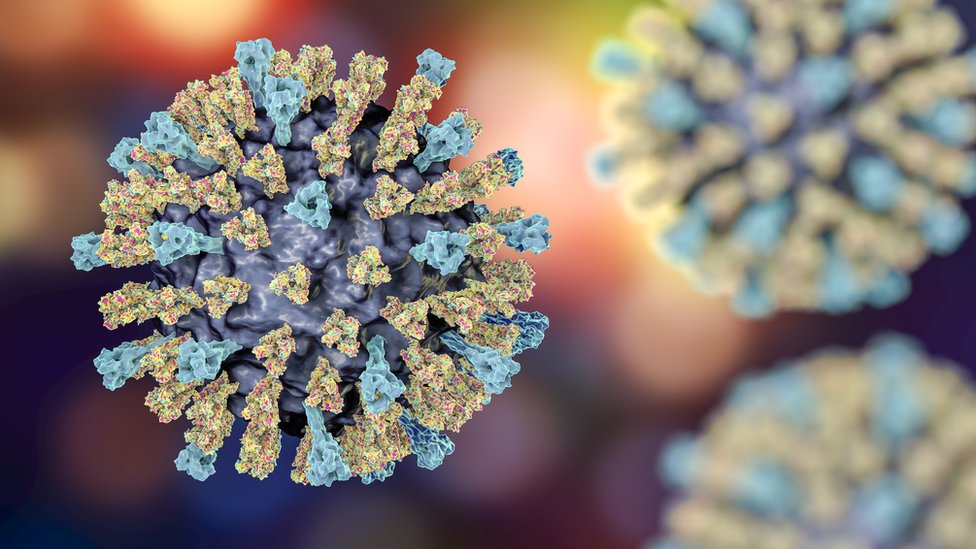

Measles is an extremely contagious virus that can be severe or even deadly, particularly for unvaccinated children.

The CDC reports that the virus is so infectious that if one person contracts it, up to 90% of people close to that individual who are not immune will also become infected.

Measles spreads through respiratory droplets from an infected person’s nose or throat. It can be transmitted through coughing, sneezing, or contact with contaminated surfaces.

Infected individuals can spread the virus up to four days before showing symptoms, and the virus can linger in the air for up to two hours after a person sneezes or coughs.

Cieslak emphasized the contagious nature of the disease, stating, “Measles is perhaps the most contagious illness we are aware of.”

The hallmark sign of measles is a rash that begins on the face and gradually spreads to cover the body. Other symptoms include fever, coughing, a runny nose, and red, watery eyes.

According to the CDC, the fever can reach more than 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Unvaccinated pregnant women, infants under 12 months old, and individuals with weakened immune systems are particularly vulnerable to severe complications if exposed to the virus.

For every 1,000 children who contract measles, one to three may die. The disease can also cause lifelong complications, such as hearing loss, deafness, and intellectual disabilities, according to the CDC.