The first round of negotiations for brand-name prescription drugs under the Medicare Part D program has concluded, setting the 2026 Maximum Fair Prices (MFP) for ten drugs.

This development stems from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which allows the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate drug prices, a shift from the previous Medicare Modernization Act that prohibited such negotiations.

The selected drugs for negotiation had to be single-source products, with specific market durations required—nine years for small molecules and thirteen years for biological products—by January 2026, when the MFPs take effect.

The IRA includes parameters that limit the negotiation outcomes. Specifically, the negotiation ceiling is set as a percentage of the non-federal average manufacturer prices (NFAMP).

For drugs approved less than 16 years ago, the ceiling is 75% of the NFAMP, while for those approved more than 16 years ago, it is 40% of the NFAMP. This ensures that negotiated prices remain within certain bounds, aiming to balance affordability with maintaining drug market dynamics.

On August 29, 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services announced the ten drugs selected for negotiation.

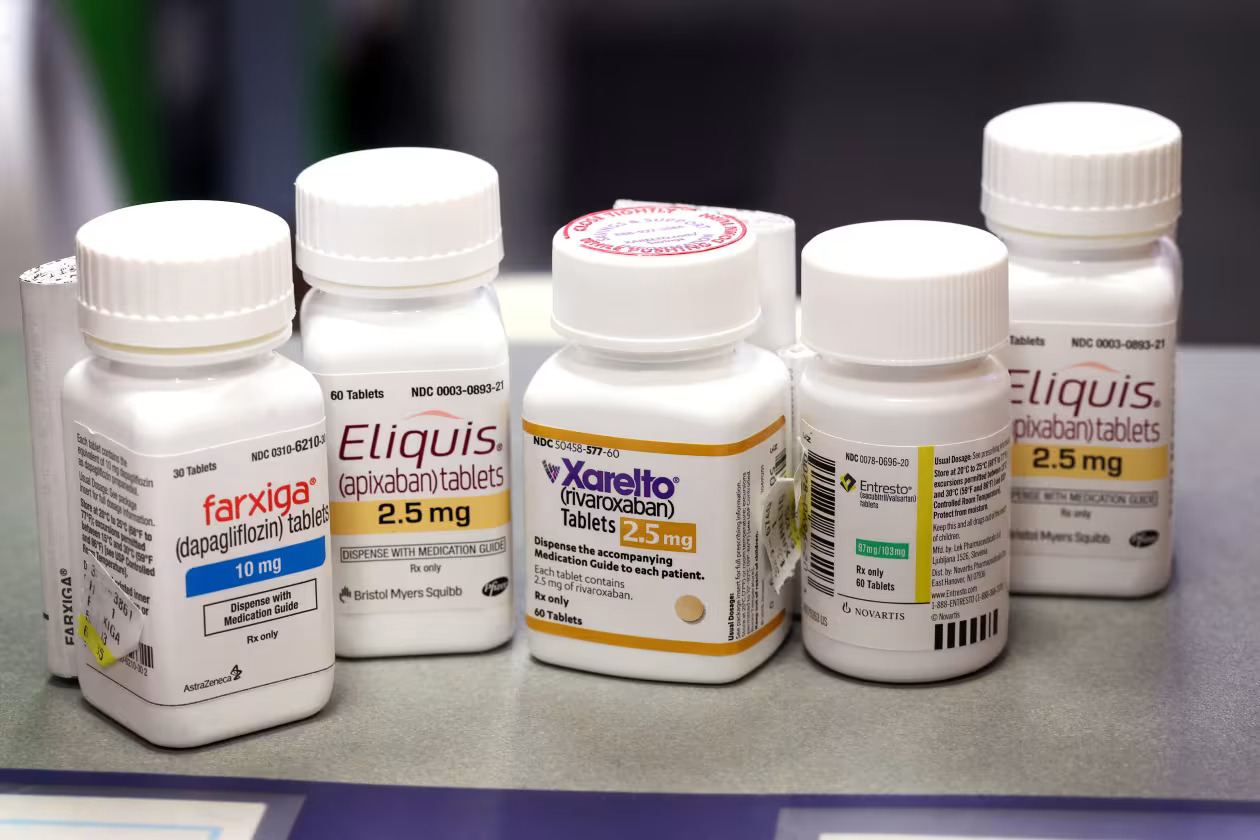

These drugs, which account for nearly $50.5 billion in gross Part D spending and are used by 9.7 million Medicare beneficiaries, include medications for conditions like blood clots, diabetes, and various forms of cancer and arthritis. The list highlights drugs with significant expenditure and extensive use among Medicare enrollees.

An analysis of the savings from the negotiations reveals that the expected reduction in spending for these drugs is about $6 billion based on 2023 prescription volumes. The analysis compared the prices realized through IRA negotiations with pre-IRA prices using publicly available data. It aimed to estimate how much lower spending would be under the new negotiated prices compared to previous arrangements.

To estimate the savings, researchers reviewed data on drug sales, manufacturer rebates, and net spending before and after the IRA negotiations. This involved combining data from CMS, MedPac, and other sources to approximate net prices and spending. The study’s methodology included using upper-end rebate estimates for a conservative approach, ensuring the baseline spending estimates were realistic.

The results showed that the total estimated savings from the negotiations amount to $6.37 billion. On average, the MFPs were about 22% lower than pre-IRA net prices. Three drugs—Enbrel, Stelara, and Eliquis—accounted for a significant portion of these savings, indicating that the negotiations were particularly effective for drugs with lower pre-IRA rebates.

The analysis also noted that negotiations led to prices that often fell below the statutory ceiling for some drugs, reflecting effective price concessions. For example, the price for Januvia increased substantially relative to pre-IRA rebates, suggesting that the negotiations were impactful even for drugs with previously substantial rebates.

The estimates presented focus on the impact of the IRA’s negotiations relative to previous practices and are based on publicly available data.

They are not intended to provide a full budgetary impact of the IRA but to illustrate how government negotiations influence drug prices compared to relying solely on Part D plans. The findings indicate that government negotiations have a significant impact, especially on drugs where market competition was previously limited.

The estimates align closely with those reported by CMS, validating the effectiveness of the negotiation process. The analysis provides a benchmark for understanding the potential savings and impact of future negotiations as the program continues to expand.