Health agencies are urgently working to determine the origins of a Mers outbreak in Saudi Arabia after three individuals with no direct contact with camels contracted the coronavirus.

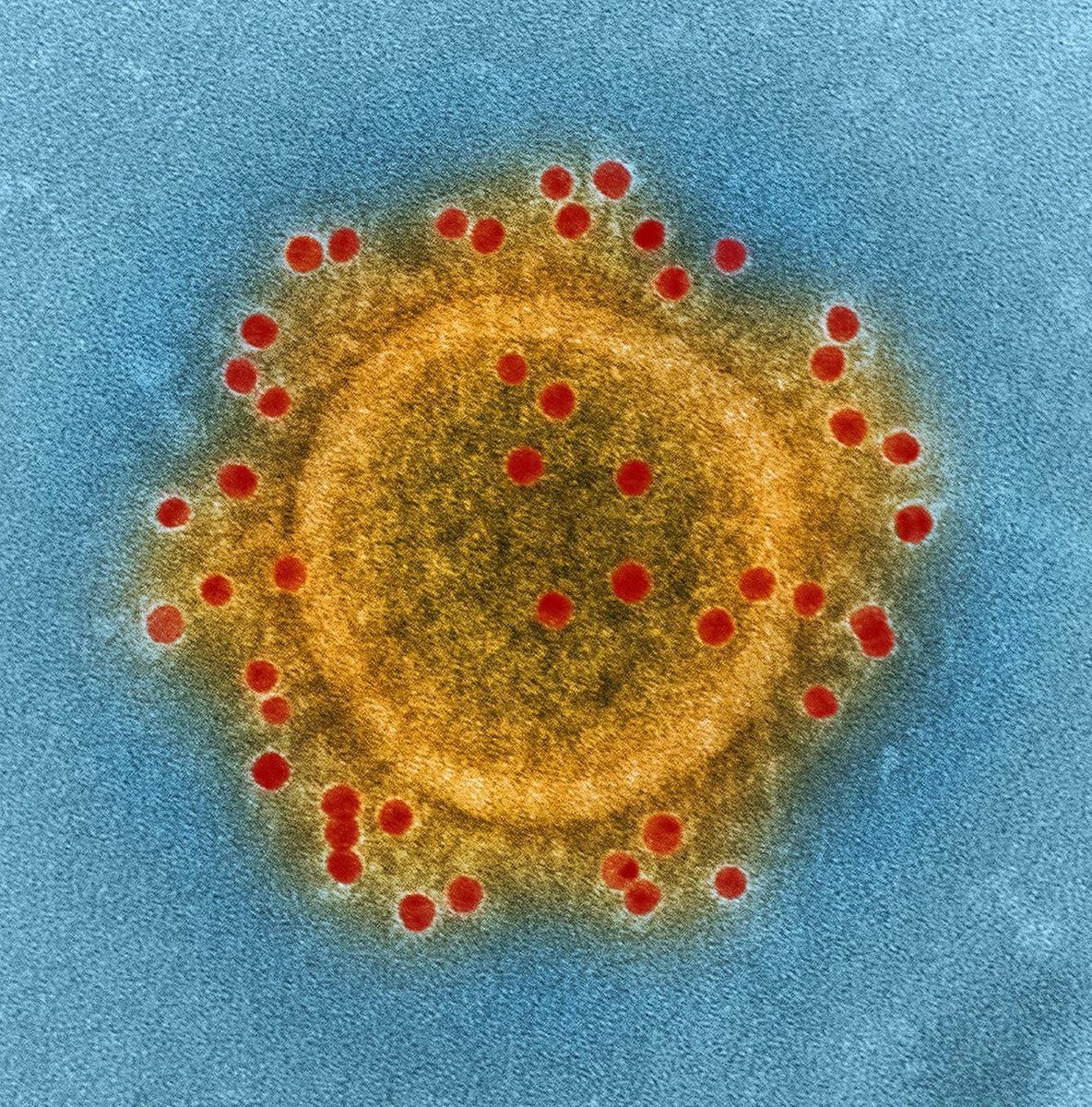

The pathogen, known as Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers), is closely related to Sars-Cov-2 but has a much higher fatality rate, with 35 percent of confirmed cases resulting in death, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The virus is typically transmitted from dromedary camels, and most previous outbreaks have been traced back to people who work closely with these mammals or their raw milk.

However, authorities have not been able to link the current outbreak, which was detected when a 56-year-old school teacher in the capital Riyadh went to the hospital in early April, to the animals. This raises concerns that milder cases might be spreading undetected.

The WHO suspects that less serious and asymptomatic cases have historically been missed, potentially affecting the case fatality rate.

“There was no clear history of exposure to typical Mers-CoV risk factors,” the UN agency stated in a disease alert this week. “Investigations, including determining the source of the infection, are ongoing.”

Mers was first identified in 2012, when it transmitted from camels to humans in Saudi Arabia, and it has since spread to 27 other countries.

The initial case in the recent outbreak involved a man with underlying health conditions who went to the hospital in early April after developing a cough, fever, and body aches. He later died from the disease.

Two other men in the same hospital, both aged 60, also tested positive for the coronavirus, prompting a broad contact tracing effort by health officials to detect further infections and prevent further spread. Dozens of people have been tested.

“Hospitals can either serve as a source of prevention or amplification of transmission,” said Dr. Saskia Popescu, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“I’ve spent a lot of time studying Mers healthcare-transmission cases and using those lessons to strengthen healthcare bioprep, and honestly, THIS is why we invest in infection prevention programs,” she wrote on X, formerly Twitter.

Mers was first detected in 2012, when it jumped from camels to humans in Saudi Arabia, and it has since spread to 27 other countries. Globally, 2,204 cases and 860 deaths have been reported, according to the WHO, with more than 80 percent of cases occurring in Saudi Arabia.

Earlier this year, Saudi Arabia also reported a fatal case in Taif, a city 500 miles west of Riyadh by the Red Sea.

There have been several large chains of transmission in healthcare facilities, including the largest outbreak outside of the Middle East in South Korea in 2015. That country confirmed 185 cases and 38 fatalities as the coronavirus spread through 24 hospitals.

While several Mers treatments and vaccines are in clinical development, unlike Covid-19, none have been carried through clinical trials and approved by regulators.

“[This is] a good reminder that we don’t have any proven antiviral treatments, vaccines, or rapid diagnostics for Mers,” said Dr. Tom Fletcher, an infectious disease specialist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

The WHO stated that the latest cases do not change the risk assessment, though it “expects that additional cases of Mers-CoV infection will be reported from the Middle East and/or other countries where Mers-CoV is circulating in dromedaries.”

The health analytic firm Airfinity, which monitors disease outbreaks globally, indicated a “high threat” for the city of Riyadh.

“Mers-CoV [is] still around and still a threat,” Prof. Peter Horby, director of the Pandemic Sciences Institute at the University of Oxford, said on X. “[Saudi Arabia] has great experience of detecting and controlling health-care associated MERS transmission – other places are less aware and less prepared.”

Prof. David Heymann, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, noted that there had been “no change in epidemiology” with these infections.

He added: “The index case is not the first case but was likely infected from the first case – they are looking for that case now.”