Researchers are proposing a new vaccine method for infants that offers sustained protection with just a single dose, even if the virus mutates. This new approach could pave the way for “universal vaccines,” according to a recent study.

Vaccines for diseases such as the flu are updated annually to address new variants, while vaccines for other diseases, like COVID-19, are updated less frequently to target dominant variants in circulation.

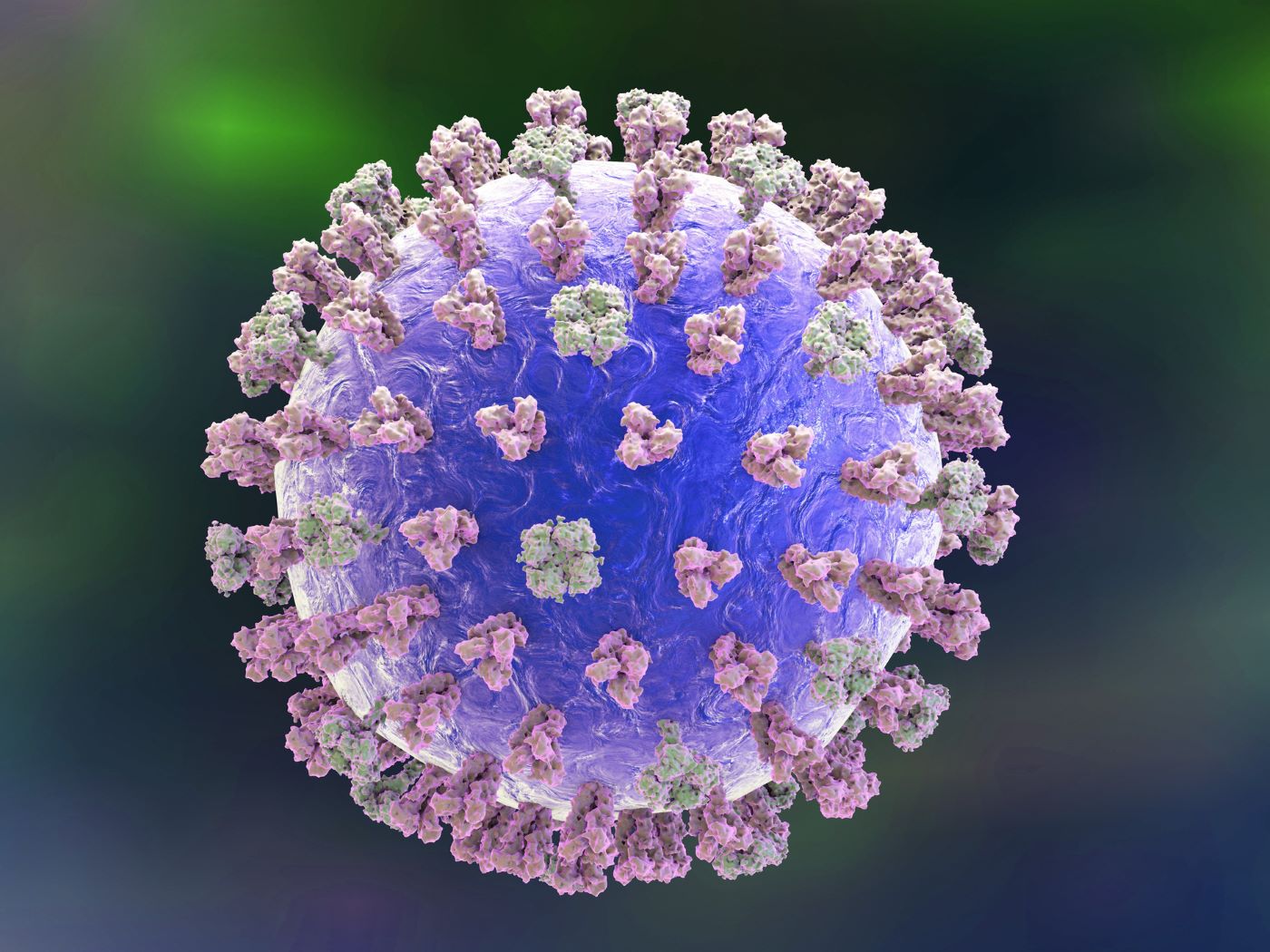

Vaccines are typically created by including a weakened or inactive version of the virus, prompting the body’s immune system to produce T-cells that attack the virus and prevent its spread.

This new vaccine strategy—tested on mice—also uses a modified version of a virus. However, instead of relying on the body’s usual immune system response, it employs small interfering RNA molecules (siRNA), which halt the spread of disease.

This allows the creation of separate vaccines targeting different diseases, according to a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diseases thrive by producing a protein that blocks the production of siRNAs, but the new vaccine strategy uses a mutant virus that can’t produce these proteins. This allows the body’s siRNAs to weaken the virus, regardless of whether it mutates and creates a new variant.

The research team from the University of California, Riverside, believes this strategy is suitable for babies, whose immune systems are still developing, because it doesn’t rely on the body’s immune response.

The researchers tested this method in baby mice and found that they also produce siRNA. When vaccinated against a mouse disease called Nodamura, the baby mice showed “rapid and complete protection” against the virus.

“It is broadly applicable to any number of viruses, broadly effective against any variant of a virus, and safe for a broad spectrum of people,” said Rong Hai, a study author and virologist at the University of California, Riverside, in a statement. “This could be the universal vaccine that we have been looking for.”

Although there are some approved vaccines for infants, vaccines for diseases like measles, COVID-19, and the flu can only be administered to individuals over the age of six months due to their immature immune systems, which can lead to a diminished response and potential lack of effectiveness.

Infants under six months have the highest risk of hospitalization due to flu infection, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). To protect this population, it is recommended that all household members and close contacts get vaccinated.

Some research indicates that vaccinated mothers may pass antibodies to fetuses through the umbilical cord and to newborns via breast milk, providing continued protection.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines given to pregnant mothers have been shown to protect infants up to six months after birth, according to the CDC.

Although no siRNA vaccines are currently approved, researchers are working on siRNA vaccines targeting COVID-19 and the flu. Previously, it was debated whether humans and other mammals use interfering RNA to kill viruses.

The same team from the University of California, Riverside, conducted research in 2013 that confirmed this theory.

They later demonstrated that flu infection prompts the body to produce interfering RNA, and they are now developing a flu vaccine using this strategy.

The researchers plan to develop this vaccine as a nasal spray rather than a shot. “Respiratory infections move through the nose, so a spray might be an easier delivery system,” Hai said.

There is already an approved nasal spray flu vaccine that is as effective as flu shots in children, according to the CDC.

Several research teams are working on nasal COVID-19 vaccines, and both China and India have approved nasal sprays as boosters.