The dengue fever outbreak in Latin America over the past three months has been staggering in scale — a million cases in Brazil in just a few weeks, a significant spike in Argentina, a state of emergency declared in Peru, and now another in Puerto Rico.

This outbreak signals a changing landscape for the disease. Dengue-spreading mosquitoes thrive in densely populated cities with weak infrastructure and in warmer, wetter environments. These conditions are expanding rapidly due to climate change.

Governments in Latin America have confirmed more than 3.5 million dengue cases in the first three months of 2024, compared to 4.5 million in all of 2023.

There have been over 1,000 deaths so far this year. The Pan-American Health Organization warns that this could be the worst year for dengue ever recorded.

The rapidly shifting disease landscape calls for new solutions. Researchers in Brazil recently announced that a clinical trial of a new dengue vaccine, delivered in a single shot, had provided strong protection against the disease, offering the only piece of good news in this scenario.

Currently, there are two existing vaccines for dengue. One is an expensive two-shot regimen, and the other can only be given to people who have already had a dengue infection.

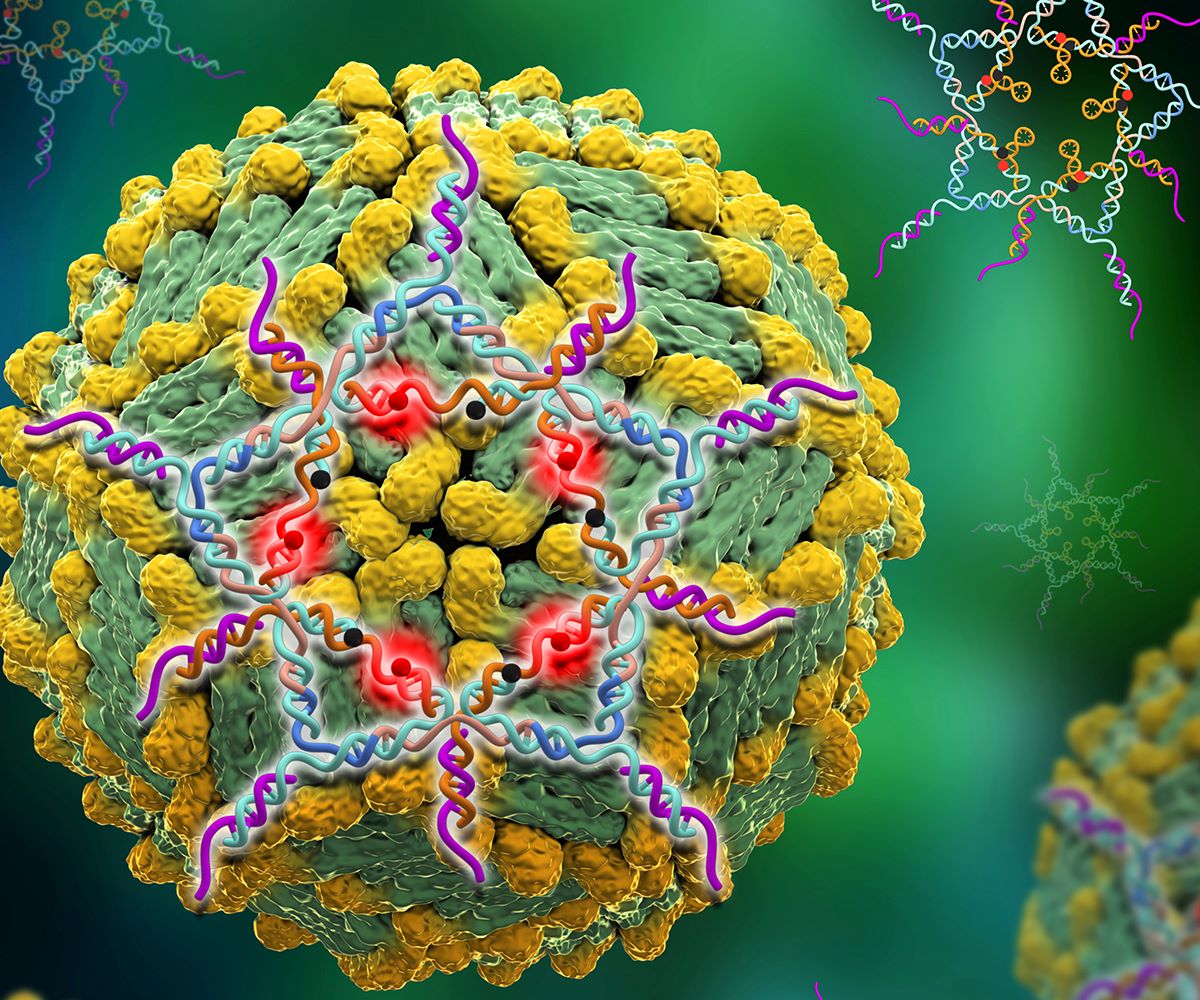

The new one-shot vaccine uses live, weakened forms of all four strains of the dengue virus. It was created by scientists at the National Institutes of Health in the United States and licensed for development by the Instituto Butantan, a large public research institute in São Paulo.

Butantan will manufacture the vaccine. It already produces most of Brazil’s immunizations and has the capacity to make tens of millions of doses of this new vaccine.

The institute plans to submit the dengue vaccine to Brazil’s regulatory agency for approval in the next few months and could begin production next year.

However, this won’t help with the current outbreak. By the time production ramps up and a national rollout begins, it might not be enough for the next outbreak either; dengue typically surges in three- or four-year cycles.

Additionally, this vaccine won’t necessarily help the rest of Latin America, as Butantan will only produce it for Brazil.

Merck & Co., a multinational drug company that also licensed the NIH technology, is developing a related vaccine for the rest of the world, but its efficacy has not yet been tested in a late-stage clinical trial.

There is also demand for a dengue vaccine beyond the Americas: Mosquitoes are spreading the disease to places like Croatia, Italy, California, and other regions that haven’t seen it before.

Areas accustomed to mild outbreaks are now facing record-breaking ones, such as Bangladesh, which had 300,000 cases last year.

Dengue, commonly known as breakbone fever due to the excruciating joint pain it causes, doesn’t always manifest symptoms. Three-quarters of those infected with dengue don’t have any symptoms, and among those who do, most cases resemble a mild flu.

However, about 5 percent of those who become sick progress to severe dengue. Plasma, the protein-rich fluid component of blood, can start leaking from blood vessels, causing shock or organ failure.

When patients with severe dengue are treated with blood transfusions and intravenous fluids, the mortality rate tends to be between 2 and 5 percent.

Without treatment — either because they don’t realize it’s dengue and delay seeking help, or because health centers are overwhelmed — the mortality rate is 15 percent.

In Brazil, the current dengue outbreak is hitting children the hardest; those under 5 have the highest mortality rate of any age group, followed by those aged 5 to 9.

Adolescents between 10 and 14 have the highest number of confirmed cases, according to the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, a national public health research center.

As clinics became overwhelmed with dengue patients in January, the Brazilian government purchased the entire global stock of a Japanese-made dengue vaccine called Qdenga.

Public health nurses are delivering it to children ages 6 to 16, but there will be enough vaccine to fully vaccinate only 3.3 million of Brazil’s 220 million people this year.

This significant national effort will protect a few million children but won’t contribute to herd immunity.

Qdenga is not cheap: It costs about $115 per dose in Europe and $40 in Indonesia. Brazil is paying $19 per dose, having negotiated a lower price for its large purchase.

Takeda Pharmaceuticals, which makes Qdenga, announced a deal last month with Biological E, a large Indian generic drug maker, to license and produce up to 50 million doses a year, part of a race to accelerate production.

The Indian vaccine should cost considerably less, but Biological E is unlikely to receive regulatory approval to market it before 2030.

The process involves transferring technology, setting up a production line, and getting a new version of even a well-known product approved by regulators.

Dengue costs Brazil at least $1 billion annually in health care treatment and lost productivity, not accounting for human suffering.

The existence of four different strains of the dengue virus complicates vaccine production and increases the risk of severe illness with subsequent infections by different strains.

Qdenga protects against all four strains, and there is hope that the new Butantan vaccine will do the same, although data so far has only shown its effectiveness against the two types circulating during the initial trial phase; more results are expected in June.

Millions more people will have been exposed to dengue when this outbreak finally subsides. They will urgently need the new vaccine more than ever.