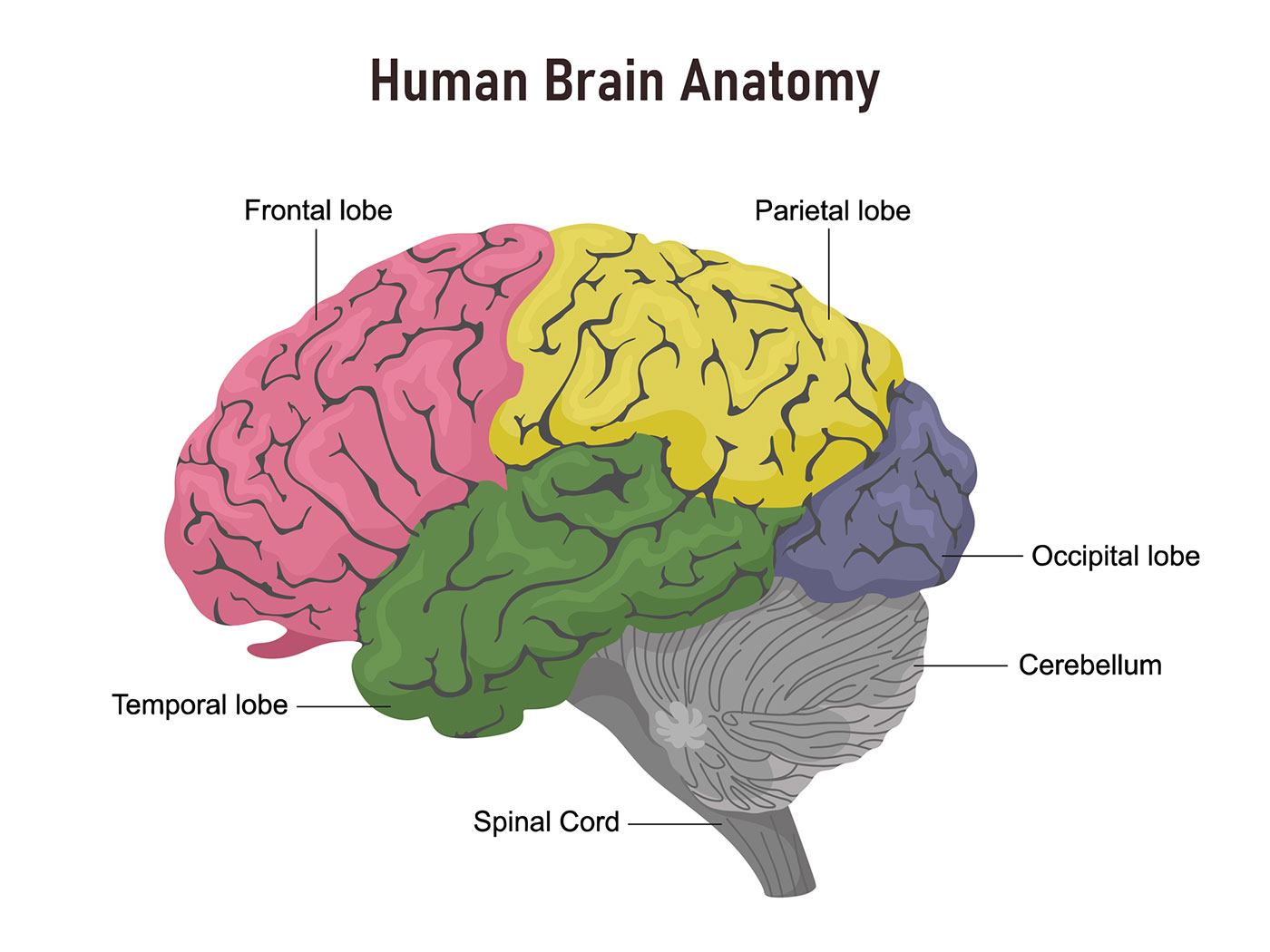

In recent decades, neuroscience has made remarkable strides, yet a crucial part of the brain remains enigmatic—the cerebellum, aptly named “little brain” in Latin, nestled like a bun at the brain’s rear.

This oversight is substantial: housing three-quarters of the brain’s neurons, the cerebellum boasts an almost crystalline organization unlike the tangled structure found elsewhere.

Encyclopedias and textbooks emphasize the cerebellum’s role in controlling body movement, a function well-established by scientific consensus. However, recent insights suggest this perspective may be narrow.

During the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, DC last November, neuroscientists convened a symposium challenging the traditional view.

They showcased new experimental techniques revealing that beyond motor control, the cerebellum regulates complex behaviors, social interactions, aggression, working memory, learning, and emotions.

The link between the cerebellum and movement has been recognized since the 19th century, with patients suffering from cerebellar trauma exhibiting significant balance and movement difficulties.

Over time, neuroscientists meticulously deciphered the cerebellum’s unique neural circuitry governing motor functions, establishing a robust understanding of its mechanics.

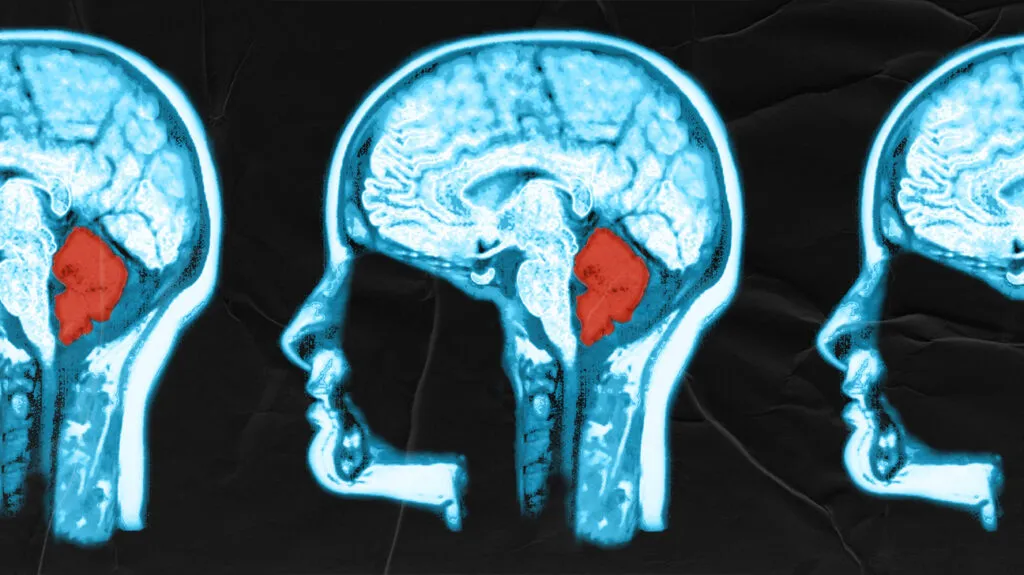

However, groundbreaking insights emerged in 1998 when neurologists reported profound emotional and cognitive impairments in patients with cerebellar damage.

For instance, a young college student underwent a personality transformation following surgical removal of a cerebellar tumor, manifesting difficulties in writing, mental arithmetic, object naming, and exhibiting inappropriate social behaviors.

Such cases puzzled researchers, challenging the notion that high-level cognitive and emotional functions solely reside in the cerebral cortex and limbic system.

Despite these clinical clues, established authorities persisted in attributing the cerebellum’s function solely to motor control. “It is kind of sad, because it has been 20 years,” lamented Diasynou Fioravante, a neurophysiologist at UC Davis, who co-organized the symposium.

Stephanie Rudolph, a neuroscientist from Albert Einstein College of Medicine and co-organizer of the symposium, noted that other neurologists had observed neuropsychiatric deficits in their patients for years.

However, the absence of anatomical evidence supporting the cerebellum’s involvement in psychological and emotional functions relegated such clinical reports to the periphery.

Now, advancements in understanding cerebellar circuitry are vindicating these case studies and reshaping prevailing beliefs.

The cerebellum’s intricate wiring, housing 50 billion neurons in a compact 4-inch structure, facilitates unparalleled integration.

This unique circuitry not only processes vast sensory inputs to coordinate movement, as seen in a dancer’s fluid grace, but also supports complex cognitive tasks and behaviors.

These include speech, which demands precise motor coordination, social cues interpretation, and emotional modulation—all crucial for effective communication.

Recent techniques have revealed long-suspected pathways connecting the cerebellum to regions controlling emotions and cognition across the brain.

This newfound connectivity challenges previous assumptions, revealing the cerebellum as a pivotal hub in brain function.

At the symposium, researchers presented compelling findings using innovative methodologies.

Studies in mice demonstrated cerebellar activation during social interactions and maze navigation, while experiments disrupting cerebellar neurons highlighted deficits in social recognition memory akin to autism spectrum disorders.

Such insights underscore the cerebellum’s role in sensory processing, particularly in social contexts.

Further clinical studies are also shedding light on how cerebellar damage affects emotional and cognitive functions, offering new diagnostic approaches.

In essence, beyond its role in motor control, the cerebellum emerges as a central player in regulating intricate social and emotional behaviors.

Its extensive neural network across the brain underscores its apt title as the “little brain,” orchestrating diverse brain functions with remarkable precision and impact.