Scientists have identified compelling evidence pointing to abnormalities in the brain and immune systems of individuals suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME).

In what is considered one of the most rigorous investigations to date, the findings begin to shed light on the biological foundations of this condition characterized by debilitating fatigue.

The study marks the first time a connection has been established between imbalances in brain activity and feelings of fatigue, suggesting these changes may be triggered by immune system irregularities.

“People with ME/CFS have very real and disabling symptoms, but uncovering their biological basis has been extremely difficult,” said Walter Koroshetz, director of NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) in the US.

“This comprehensive study of a small group of individuals identified several factors likely contributing to their ME/CFS.”

The study involved only 17 patients, and further validation in a larger cohort is necessary before these findings can be considered a roadmap for new treatments.

Moreover, it remains unclear how applicable these findings are to long Covid, given that participants were recruited and evaluated before the pandemic.

Nonetheless, scientists view this work as a long-overdue deep go the biological underpinnings of the condition.

“This is such an important paper and one I am so pleased to see come out,” commented Prof Karl Morten, who studies ME/CFS at the John Radcliffe hospital, University of Oxford, and was not involved in the study.

“We’ve had lots of smaller studies suggesting problems with specific cells, but no one has previously examined everything in a single patient.”

Patients selected for the study, from an initial pool of 300, all had a history of infection preceding the onset of illness. They spent a week at an NIH clinic undergoing a range of physiological assessments.

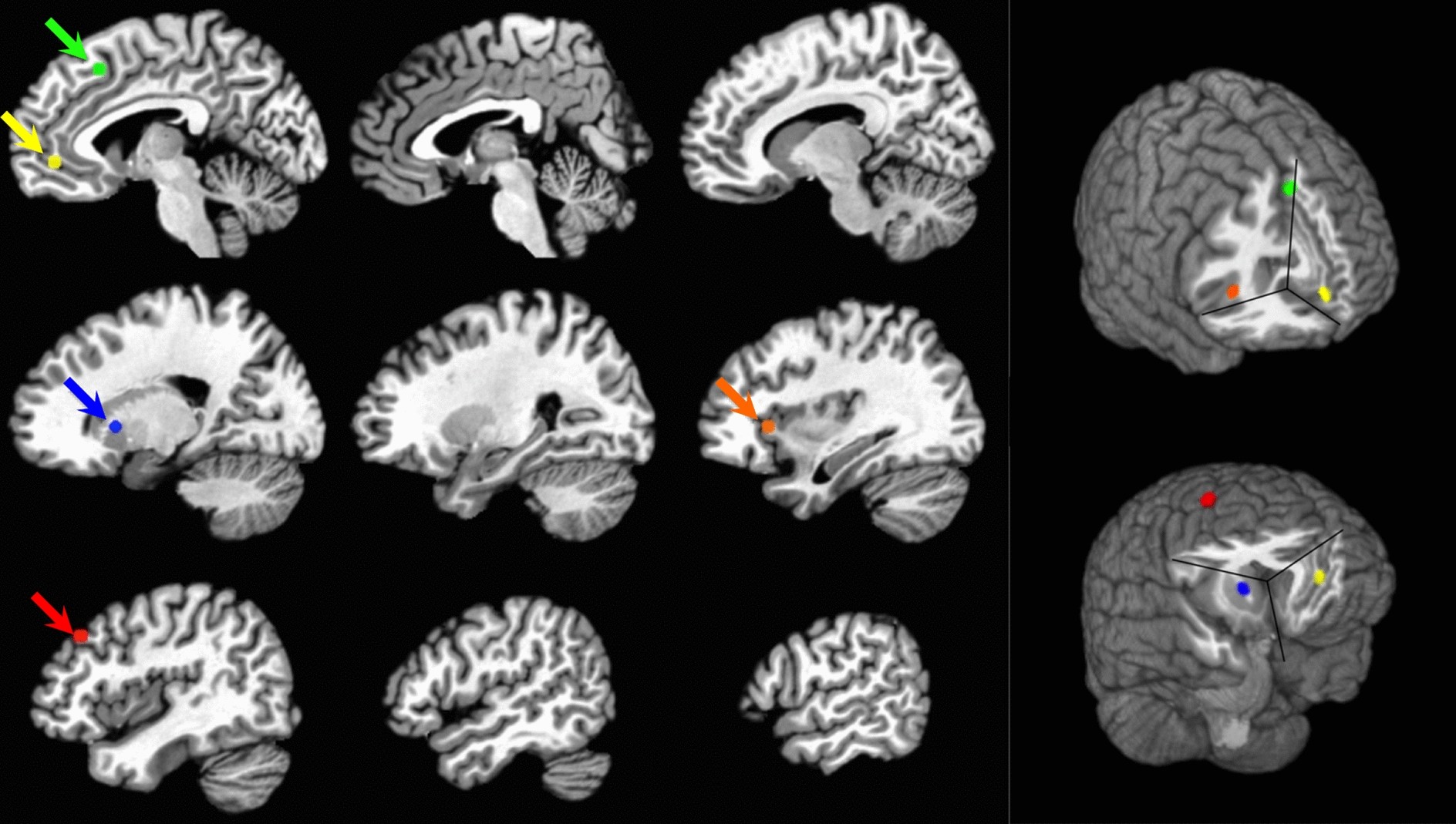

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans revealed lower activity in the temporal-parietal junction (TPJ) among ME/CFS patients, a region implicated in decision-making related to exertion, which could explain fatigue.

The motor cortex, responsible for directing bodily movements, also showed abnormal activity during fatiguing tasks, despite no signs of muscle fatigue.

These findings suggest that fatigue in ME/CFS may stem from dysfunctional brain regions influencing the motor cortex, altering patients’ capacity for exertion and their perception of fatigue.

“We may have pinpointed a physiological focal point for fatigue in this population,” said Brian Walitt, associate research physician at NINDS and lead author of the study published in Nature Communications.

“Fatigue appears to result from a discrepancy between perceived and actual physical capabilities, rather than mere physical exhaustion or lack of motivation.”

Morten emphasized that discovering brain function abnormalities does not imply that patients are psychologically causing their illness or have any control over it.

“The brain can respond to stimuli and affect the body,” he noted. “The issue lies in the brain’s physical and biochemical malfunction, caused by the illness itself, not by the patient.”

The study also noted increased heart rates and delayed blood pressure normalization post-exertion among patients.

Furthermore, changes observed in patients’ T cells from cerebrospinal fluid suggest ongoing immune responses, possibly indicating failure to resolve an infection or presence of a chronic, undetected infection.

The authors propose a potential cascade of events starting with persistent immune activation, leading to central nervous system changes, biochemical alterations in the brain, and ultimately affecting specific brain structures that regulate motor function and fatigue perception.

“We believe immune activation influences the brain in various ways, causing biochemical shifts and subsequent effects on motor, autonomic, and cardiorespiratory functions,” explained Avindra Nath, clinical director at NINDS and senior author of the study.

Scientists have hailed these findings as a significant stride toward uncovering the biological roots of the illness.

Historically lacking a clear biological basis, ME/CFS has often resulted in dismissal, stigma, and limited treatment options for patients.