The disease known as syphilis, which ravaged Europe in the 15th century and continues to be a global health concern, has a complex history and origins that have sparked considerable debate and historical stigma.

Initially dubbed the “French disease” by the English, Germans, and Italians, and alternately named by others as the “German disease” or the result of national blame games like the Russian attribution to Poles, syphilis has long been associated with Europe.

The first documented epidemic occurred when the French army, invading Naples in Italy, succumbed to the disease, hence the moniker “Neapolitan disease” in France.

The origins of syphilis have been elusive and challenging to study, but a prevalent theory linked its emergence in Europe to the return of Christopher Columbus and his expeditions from the Americas.

However, a recent study published in Nature challenges this notion, proposing a more intricate narrative.

Paleopathology, the study of ancient pathogens preserved in bones, dental plaque, and mummified bodies, has provided crucial insights.

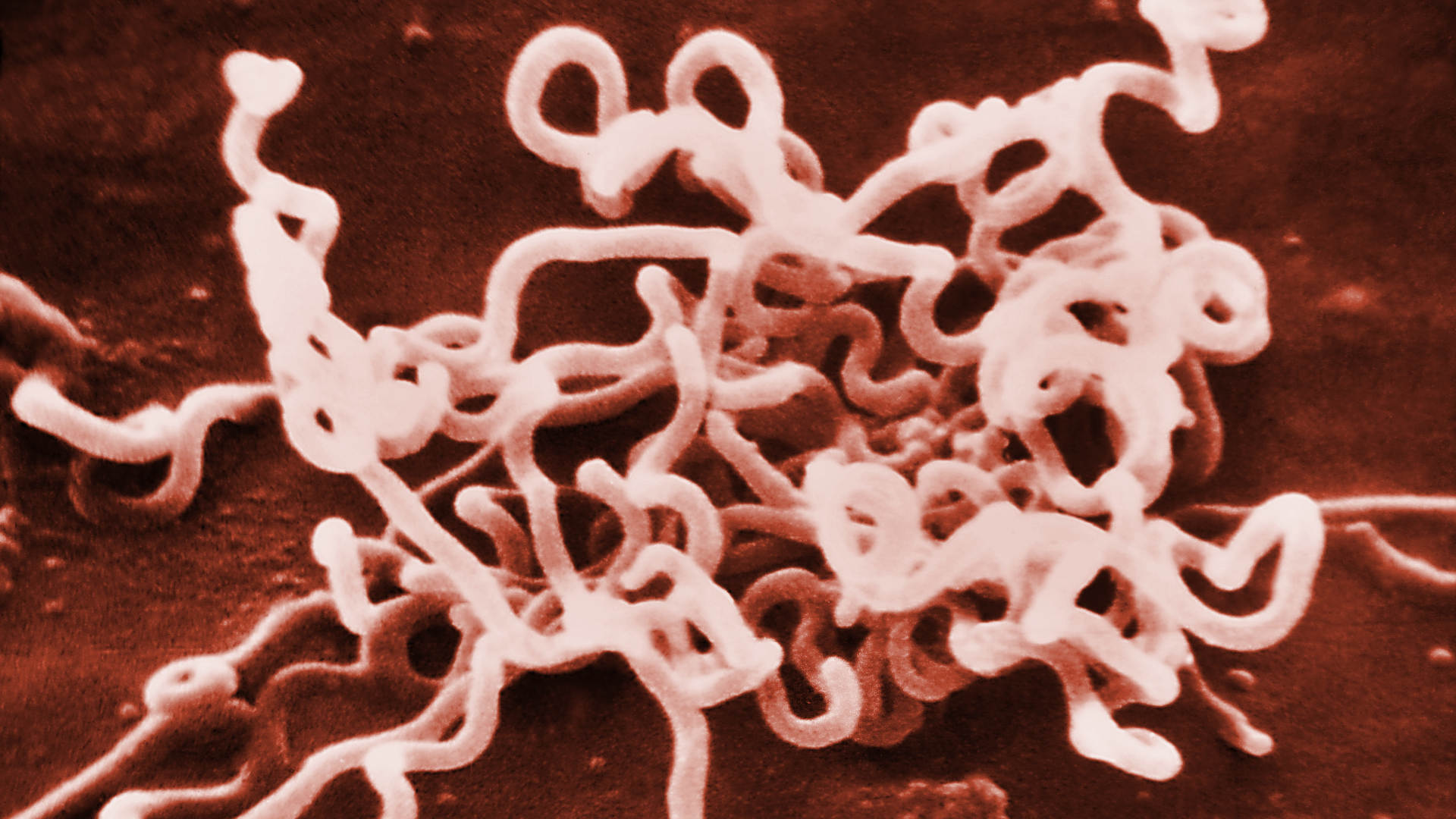

Researchers conducted genetic analyses on 2,000-year-old bones unearthed in Brazil, uncovering the earliest known genomic evidence of Treponema pallidum, the bacterium causing syphilis and related diseases. Remarkably, these findings predate the first trans-Atlantic contacts.

“This study is incredibly exciting because it is the first truly ancient treponemal DNA that has been recovered from archaeological human remains that are more than a few hundred years old,” noted Brenda J. Baker, an anthropology professor at Arizona State University.

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a bacterium capable of causing severe physical deformities, blindness, and neurological impairments if left untreated.

Historically stigmatized as a sexually transmitted disease, syphilis has been blamed on neighboring populations and countries during outbreaks.

Molly Zuckerman, a professor specializing in bioarchaeology, underscored the complexity of studying both the disease and its causative agent.

Despite advancements, such as the first successful culture of T. pallidum in 2017, syphilis remains among the least understood bacterial infections.

The sudden onset of syphilis epidemics in Europe during the late 15th century initially suggested a New World origin post-Columbus.

Some hypothesized that the bacterium, initially mild in nature, may have gained virulence over time. However, the study’s findings challenge this, indicating that treponemal diseases, including bejel with similar symptoms to syphilis, were present in the Americas well before Columbus’s voyages.

Verena Schünemann, a study author from the University of Zurich, clarified that while the findings do not definitively support Columbus importing venereal syphilis to Europe, they do suggest complex pre-Columbian interactions.

The recovered genome traced T. pallidum’s evolution to infect humans back as far as 12,000 years ago, possibly brought to the Americas by early human migrations from Asia.

“This study shows that the story is way more complex than the Columbian hypothesis could have ever imagined,” Schünemann commented.

Mathew Beale, a senior scientist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, emphasized that the study’s findings neither confirm nor refute the Columbian hypothesis directly. Instead, they suggest broad distributions of treponemal diseases globally, predating Columbus.

Further research into ancient genomes worldwide may shed more light on the subspecies of Treponema present in Europe and the Americas before Columbus’s era, addressing critical questions about disease transmission and human migration.

“The modern tools for extracting and sequencing DNA from ancient samples have significantly advanced our understanding of Treponema,” noted Sheila A. Lukehart, an expert in infectious diseases and global health.

The study underscores the importance of paleopathology in unraveling ancient disease origins and their impact on human history and health.