More than 25% of individuals who suffer a stroke experience a peculiar condition: they lose conscious awareness of half of their visual field.

For instance, after a stroke affecting the right hemisphere of the brain, a person might only eat food on the right side of their plate, seemingly unaware of the left side.

They might observe only the right half of a picture, completely overlooking individuals on their left side. Interestingly, these stroke survivors can emotionally respond to the entire scene or image, suggesting that their brains register the information broadly, even though they are consciously aware of only half.

This condition, known as unilateral neglect, underscores a fundamental question in neuroscience: what distinguishes the perception of something from conscious awareness of perceiving it?

Often, our brains process information that we do not consciously acknowledge, such as scrolling past a shoe store on social media and later searching online for shoe sales.

Researchers from Hebrew University of Jerusalem and University of California, Berkeley, have identified a potential region of the brain where sustained visual representations are maintained for several seconds after perception. Their findings were published this month in Cell Reports.

“Our study focuses on the everyday experience of consciousness, particularly visual experience, from the moment one wakes up to when they go to sleep,” explained Gal Vishne, lead author and graduate student at Hebrew University.

While these findings do not yet explain why individuals may be unaware of what they perceive, they hold promise for practical applications.

For instance, understanding how consciousness operates could help doctors determine whether coma patients remain aware of their surroundings, potentially guiding treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

Leon Deouell, senior author and professor of psychology at Hebrew University, expressed that his scientific interest was initially sparked by stroke patients with unilateral neglect.

He emphasized the broader implications of understanding conscious awareness: “What is needed for us not only to sense information but also to subjectively experience it?”

Robert Knight, another senior author and professor at UC Berkeley, added, “We are adding a piece to the puzzle of consciousness—how information remains in the mind for us to act upon.”

For decades, studies of brain electrical activity have primarily focused on the initial surge of neural response upon perceiving something, lasting mere milliseconds.

However, researchers found that visual areas of the brain maintain a sustained representation of perceived stimuli at a lower level of activity for longer periods, up to several seconds.

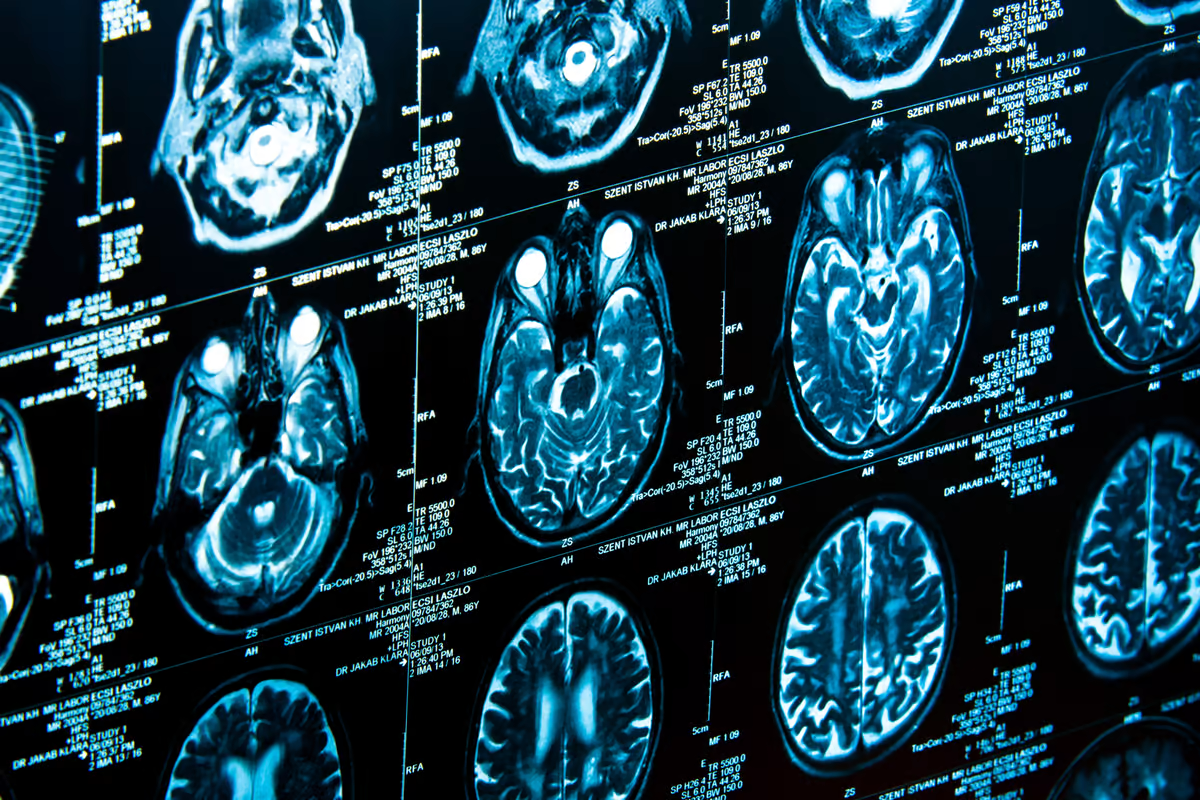

Using electrodes implanted on the brain surface of 10 patients undergoing surgery for epilepsy, the researchers recorded neural activity while presenting various images for different durations.

This method allowed them to observe and analyze neural responses in detail, revealing that the occipitotemporal area of the visual cortex sustains information despite decreasing activity levels over time.

“The frontal cortex detects novel stimuli, whereas higher-level sensory regions maintain ongoing representations,” Deouell explained. These findings suggest that conscious awareness may arise when the prefrontal cortex accesses sustained activity in visual regions of the brain.

Looking ahead, Deouell and Knight plan to investigate electrical activity associated with consciousness in other brain regions, such as those involved in memory and emotions. Their ongoing research aims to further elucidate the complex mechanisms underlying human consciousness.