The vast majority of individuals in the United States who have tested positive for hepatitis C remain untreated due to the high costs of oral antiviral therapies and the bureaucratic hurdles imposed by insurance plans, federal health officials disclosed on Thursday.

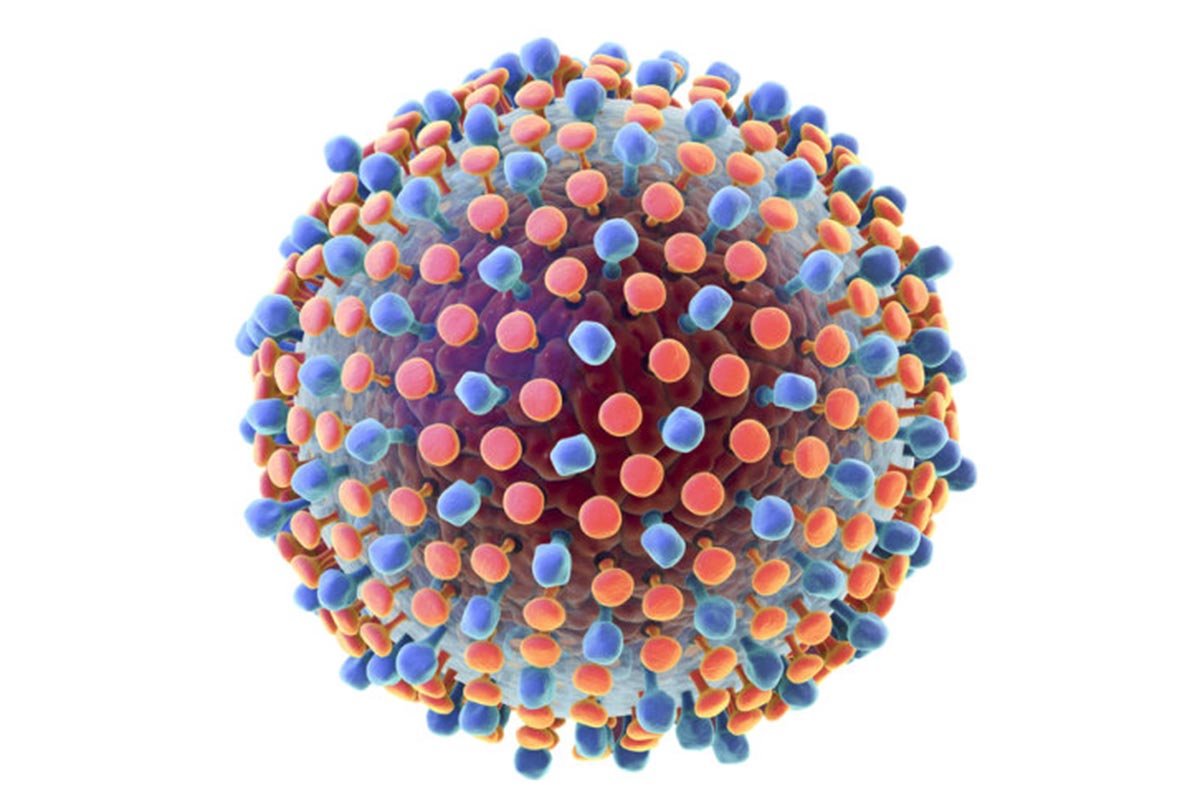

Hepatitis C, often known as the silent killer due to its initial asymptomatic nature, can progress over time to cause severe liver damage, liver cancer, liver failure, and potentially death.

The virus spreads primarily through contact with infected blood, particularly via shared needles and other drug-injection equipment.

Breakthrough oral antiviral medications developed by Gilead Sciences and Abbvie have been available in the U.S. market for nearly a decade.

These pills, taken once daily for eight to 12 weeks, successfully cure over 95% of hepatitis C cases.

Despite the existence of these effective treatments, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published Thursday revealed that only one-third of the 1 million adults in the U.S. who tested positive for hepatitis C between 2013 and 2022 have been cured.

Health officials estimate that another million Americans are infected but unaware of their status.

In 2020 alone, hepatitis C was a contributing factor in nearly 15,000 deaths, according to CDC data.

“Thousands of people are dying every year in our country, and many more are suffering from an infection that has been curable for more than 10 years,” said Dr. Jonathan Mermin, director of the CDC’s HIV and viral hepatitis division, during a press briefing on Thursday.

The Biden administration has proposed an $11 billion funding request to Congress aimed at implementing a national program to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030.

Dr. Francis Collins, leading the initiative at the White House, emphasized that the program would save thousands of lives and ultimately pay for itself by reducing healthcare costs.

Health officials cited two primary barriers to treatment: the stringent requirements imposed by health insurance plans and the prohibitively high cost of medications, which can reach up to $24,000 per patient.

Dr. Carolyn Wester, head of the CDC’s viral hepatitis division, noted that some insurers require complex preauthorization processes before patients can access treatment, in addition to limiting which healthcare providers can prescribe the medications.

Collins highlighted the challenges faced by community health centers that treat uninsured patients, noting that only one in four uninsured adults diagnosed with hepatitis C have received treatment.

Even state Medicaid programs, Collins explained, impose onerous conditions such as evidence of liver disease, sobriety, and specialist involvement.

The high cost of medications has posed difficulties for Medicaid in treating all infected individuals, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Under Biden’s proposal, the federal government would negotiate lump-sum payments with pharmaceutical companies like Gilead and Abbvie for their drugs.

Subsequently, these companies would provide the medications free of charge to uninsured individuals, state Medicaid programs, prison systems, and residents of Native American reservations.

The proposal builds on a successful model introduced by Louisiana in 2019, where the state paid Gilead subsidiary Asegua Therapeutics a lump sum to supply drugs over five years, thereby curing nearly all Medicaid patients and incarcerated individuals.

Collins also mentioned ongoing efforts by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve a rapid hepatitis C test.

This test, capable of providing a diagnosis within an hour, would facilitate same-visit diagnosis and treatment for patients.