Emerging research suggests a potential link between endometriosis, a chronic disease causing debilitating pain, and bacteria commonly found in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract.

Endometriosis has puzzled physicians for years. This condition affects roughly 10 percent of women worldwide and more than 11 percent in the United States.

While scientists have theorized about possible triggers, the root cause remains largely unknown, limiting treatment options.

In a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Japanese researchers examined vaginal swab samples from 155 women — 76 healthy women and 79 women with endometriosis.

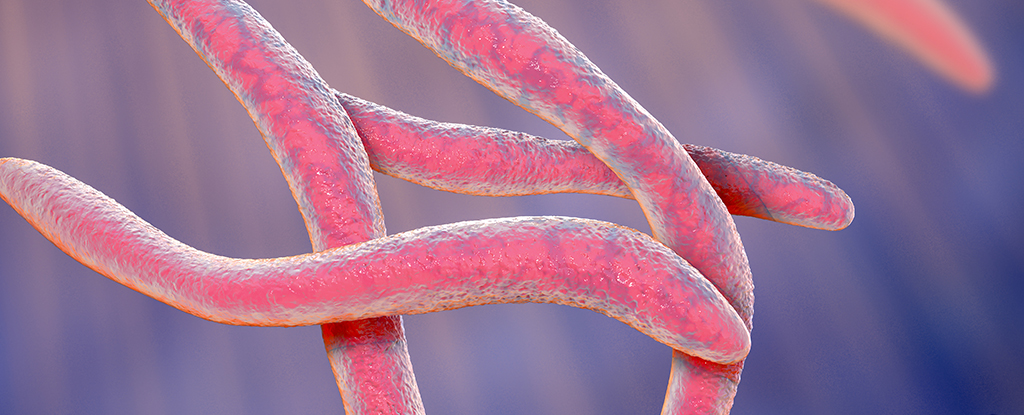

They discovered that 64 percent of women with endometriosis tested positive for bacteria in the genus Fusobacterium in their uterine lining, whereas less than 10 percent of healthy women carried the bacteria there.

Following this initial discovery, researchers used mouse models to further investigate the link.

They observed an increase in endometriotic lesions after injecting mice with Fusobacterium. When the mice were given antibiotics, the number and weight of the lesions declined significantly.

Some strains of Fusobacterium are harmless, but others can cause severe infections in humans.

Fusobacterium is associated with oral diseases such as periodontitis and tonsillitis, but this is the first time the bacteria have been linked to issues with the female reproductive system.

Yutaka Kondo, a study author and cancer biologist from Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan, described the discovery as groundbreaking in women’s health care.

“Previously, nobody thought that endometriosis came from a bacterial infection, so this is a very new idea,” Kondo said.

Endometriosis is a condition where tissues similar to those in the uterine lining grow outside the uterus.

The lesions cause excruciating menstrual cramps, digestive issues, and can lead to infertility.

Previous research attributed the affliction to retrograde menstruation, a genetic predisposition, or hormones, though the exact cause remains unknown.

Birth control, a hormonal option that stops menstruation, is one of the treatments for endometriosis, but it is only effective while being taken.

Once a person stops the medication to try to get pregnant, the pain resumes. Since 30 to 50 percent of people with endometriosis experience infertility, they may spend months trying to conceive while enduring severe pain.

The only “cure” for endometriosis is removing a person’s reproductive organs.

“Medicine puts a Band-Aid on it,” said Allison K. Rodgers, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Fertility Centers of Illinois, who was not involved with the study.

“I can give you medicine to stop your periods; I can give you birth control pills; I can give you pain meds; I can cut it out with surgery,” she said.

“But we haven’t figured out the why, and once we start figuring out the why, we’ll be able to design targeted approaches for treatment.”

Kondo emphasizes that while no conclusive treatments can be derived from this new study, he hopes the discovery will spur research into more potential therapies.

“If this indeed holds true for other patients, it may be worth investigating the microbiome of patients with endometriosis from a larger population and assessing whether there’s a mix of different infectious agents that cause inflammation and change the tissue to behave like endometriosis,” said Raymond Manohar Anchan, director of the Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Research Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Anchan, who specializes in endometriosis, said he would be “surprised” if this were a complete correlation and that it “warrants more investigation.”

Anchan and Rodgers also note that the sample size is small and that the study results do not justify automatically prescribing antibiotics to treat endometriosis.

Still, Rodgers describes the results as “exciting, even though they’re in their infancy.” She and other experts see it as a jumping-off point for further research.

“Studies like this are exciting — for every 1,000, probably only one goes on to make a giant discovery,” Rodgers said. “But once we can figure out why some people’s endometrial cells are extra sticky, we can look at targets for a cure.”